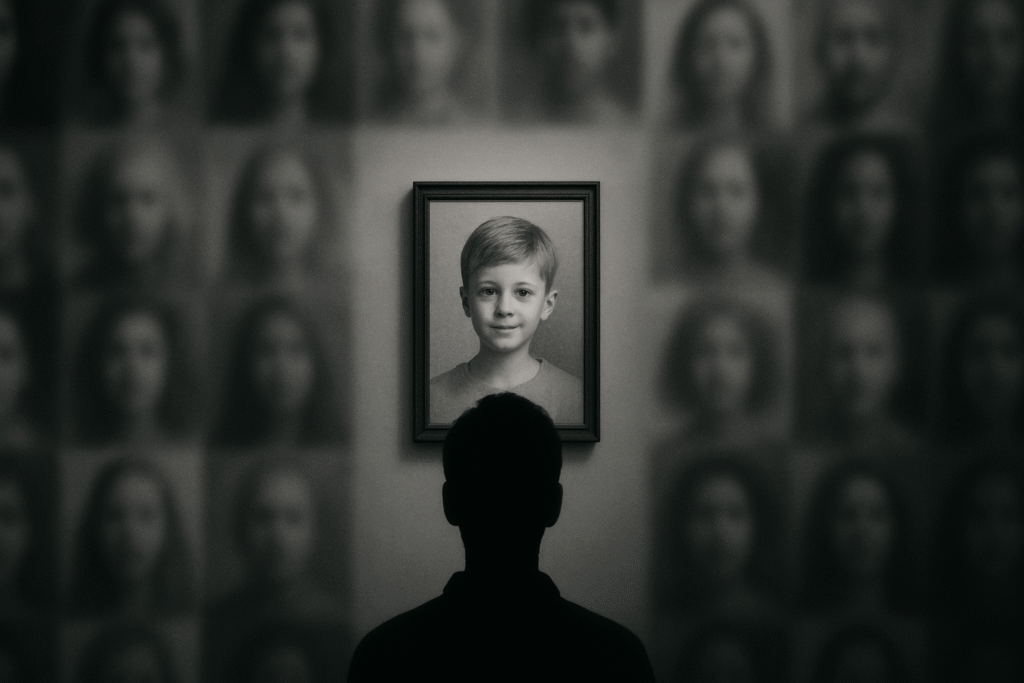

Fun Fact: In a famous study, people donated twice as much money to save one child than to save eight—simply because the single child had a name and a photo.

Imagine this: You see a photo of a little girl named Aisha, eyes wide and frightened, standing in the rubble of a war zone. You feel a pang. You might cry. You might donate.

Now imagine hearing that 10,000 children just like her have died in the same conflict. You pause. You feel… numb. Maybe overwhelmed. Maybe helpless.

This is not callousness. It’s something psychologists call the empathy gap—our deep, strange tendency to care more for individuals than for entire groups. And in a world constantly asking for our compassion, it raises a hard question: Why does one life move us more than a million?

The Power of One: The Identifiable Victim Effect

Human empathy isn’t logical. It’s emotional, visual, and personal. Researchers call this the identifiable victim effect—the finding that people are more likely to aid a single known individual than an anonymous group.

In a 2007 study by psychologist Paul Slovic, participants were shown a charity appeal. One version described a girl named Rokia, complete with her photo and story. The other listed facts are about millions of starving children. The result? People gave significantly more to help Rokia.

The conclusion? We are wired to feel for people—not statistics.

The Math Problem of the Heart

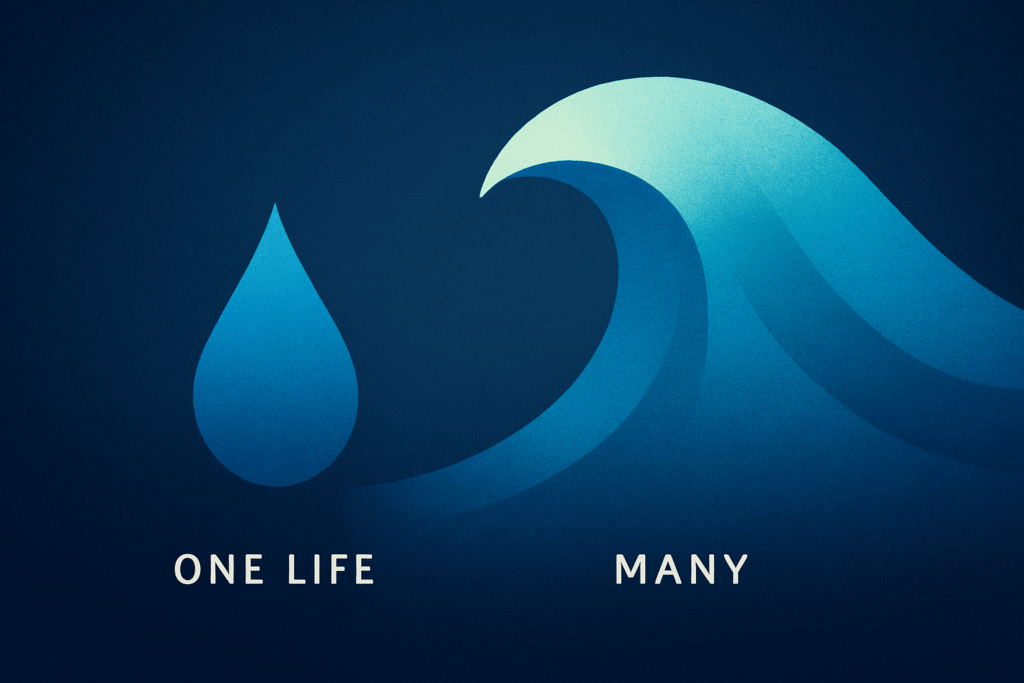

It gets even more uncomfortable. Slovic’s later studies showed that empathy doesn’t just plateau with large numbers—it actually drops.

Here’s how people actually respond to numbers of suffering individuals:

- 1 person in need → high empathy

- 2 people in need → slightly less empathy

- 100 people in need → emotional shutdown

This is called psychic numbing. The more victims we see, the less we emotionally engage. It’s as if our empathy circuits get overwhelmed and start to shut down.

Why Our Brains Struggle with Groups

There are a few evolutionary reasons behind this empathy gap:

We Evolved in Small Groups

Our ancestors lived in tribes of 50–150 people. Evolution shaped our brains to focus on individuals—not abstract masses.

Faces Matter

Our emotional brain, especially the amygdala, responds to facial expressions. A single photo of a crying child activates it. A bar graph of famine victims? Not so much.

Responsibility Diffusion

When many people are suffering, we feel less personal responsibility. “Surely someone else will help,” our subconscious tells us. This is known as the bystander effect—a well-documented psychological phenomenon.

Case Study: Syrian Refugee Crisis vs. One Child on a Beach

In 2015, news broke of the Syrian refugee crisis. For years, stories and statistics flooded headlines: over 13 million displaced. But the real global outcry didn’t begin until one image appeared—the lifeless body of 3-year-old Alan Kurdi on a Turkish beach.

Suddenly, the crisis had a face. A name. A child.

Donations surged. Governments made emergency statements. People cried.

That’s the empathy gap in action.

The Problem with Our Good Intentions

This emotional bias has real consequences:

- Charity priorities: Organizations that feature individual stories raise more money—even if they serve fewer people overall.

- Media coverage: Tragedies involving individuals get more airtime than disasters affecting entire populations.

- Policy decisions: Politicians often act faster on “human interest” stories than on data-driven warnings.

It’s not that we don’t care. It’s that our feelings are built for connection, not calculation.

Can We Close the Empathy Gap?

So, are we doomed to care only when we see a child’s eyes?

Not necessarily. Awareness is the first step. Here’s how we can start to bridge the gap:

Combine Emotion with Information

Effective storytelling uses both the power of the personal and the scale of the problem. Start with one story—then zoom out.

Frame Numbers Differently

Instead of saying “100,000 people died,” say, “That’s one person every five minutes.” Context makes numbers human.

Engage with Long-Term Stories

Sustained empathy comes from sustained attention. Instead of only reacting to viral moments, we need to build empathy into our education, our media, and our institutions.

New Tools for Empathy

Some organizations and tech firms are trying to fix the problem.

Charity: Water, a U.S.-based nonprofit, pairs donors with individual recipients using GPS and storytelling updates—so that people giving to a community still feel a personal connection.

Be My Eyes, a Denmark-based app that connects blind users with sighted volunteers in real time, reminds us that empathy doesn’t have to be abstract—it can be a daily act.

Even social media, often blamed for compassion fatigue, can be used to personalize large issues. A single reel, a photo, or a voice note can build bridges that numbers never could.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

From climate change to refugee crises, from pandemics to poverty—our biggest problems are mass problems. And yet, our instincts are built for individual compassion.

That mismatch could mean the difference between action and apathy.

If we want to solve collective problems, we have to learn how to feel for the collective—without losing our human warmth.

Conclusion: Scaling the Heart

The empathy gap is not a flaw. It’s a feature of our emotional system—one that evolved to help us care for those closest to us.

But we live in a world that demands more. More compassion. More attention. More action for people we’ll never meet.

The challenge isn’t to feel less for one life. It’s to feel just as much for thousands—and to teach our hearts to stretch wider than they were ever asked to in the past.

Because a million lives matter as much as one, we just have to remind our minds—and our hearts.

Author’s Note

This blog explores a hard truth about human emotion—not to shame our instincts, but to stretch them. If we want a kinder world, we’ll need to build systems that support compassion at scale, not just at arm’s length.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.