Fun fact: Viruses, which cause everything from the common cold to COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019), are not technically considered “alive” by many biologists.

It seems like the simplest question in science: what makes something alive?

We all think we know the answer. Dogs are alive. Rocks are not. Plants are alive. Plastic is not. But when you press deeper, biology starts to stammer. The truth is that science still struggles to pin down a clear definition of life.

This blog explores the puzzle at the heart of biology’s identity crisis: What makes something alive? Biology’s struggle to define life is not just a matter of philosophy—it touches medicine, space exploration, and even how we see ourselves.

The Classic Checklist of Life

Traditionally, biology textbooks give us a handy checklist. Something is alive if it:

- Grows and develops

- Reproduces (on its own)

- Responds to stimuli

- Maintains homeostasis (internal balance, like regulating temperature)

- Uses energy (metabolism)

- Evolves over time

By this list, a cat is alive, a tree is alive, and a human is alive. Easy.

But here’s the catch: viruses, prions, and even some computer programs challenge every box on that list. Biology’s “rules” about life start to look more like guidelines.

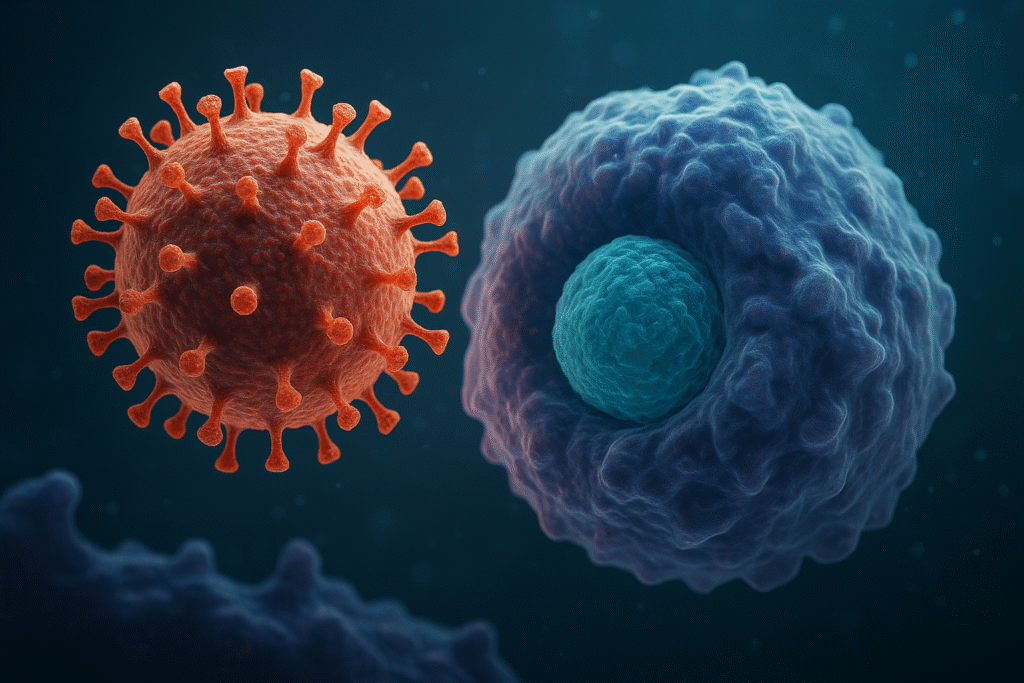

Viruses: The Gate Crashers

Viruses are the troublemakers in this debate.

Outside a host, a virus is just a particle of protein and genetic material—completely inert. No metabolism, no response to stimuli, nothing. But once inside a living cell, viruses hijack their host’s machinery to reproduce, adapt, and evolve.

So, are viruses alive?

Biologists are split. Some say no—they’re more like clever molecular machines. Others argue that life isn’t about independence, but about systems that can replicate and evolve. By that standard, viruses are very much alive.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: if viruses don’t count, then life itself may not be as clear-cut as we think.

The Alien Problem

The debate gets even stranger when we look to the stars.

NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration), which searches for extraterrestrial life, defines life as “a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution.”

This sounds neat—until you realize it excludes mules (which are sterile hybrids and can’t reproduce) but might include some computer simulations. Imagine telling a farmer that his mule isn’t alive, but a line of code could be.

That’s biology’s nightmare: if we can’t define life on Earth, how will we recognize it on Mars or Europa?

Life as a Continuum, Not a Category

Some scientists argue that our mistake is trying to draw a hard line where none exists. Instead of “alive” or “not alive,” life may exist on a spectrum.

Think of fire: it consumes energy, grows, and spreads. Yet we don’t call fire alive, because it doesn’t carry genetic information or evolve in a Darwinian sense. Viruses, prions, synthetic cells, and AI all sit somewhere in that messy middle ground.

Maybe “life” isn’t a strict definition, but a gradient—like colour. Where does red become orange? Where does “not life” become “life”?

Case Study: Synthetic Biology

In 2010, the J. Craig Venter Institute (a genomics research company) announced it had created the first synthetic cell by building a bacterial genome in the lab and transplanting it into another cell.

Was that life created? Or was it just “life modified”?

The achievement blurred the lines even further. If humans can assemble DNA and spark activity in a lab, are we creators of life—or just engineers of complex chemistry?

Life in a Computer?

Here’s where things get provocative. Some researchers in artificial life argue that a sufficiently complex computer simulation could count as alive.

If life is about processing information, adapting, and evolving, then why should it matter whether the “substrate” is carbon molecules or silicon chips?

It’s unsettling to think your smartphone could one day contain something biologists might have to call “alive.”

So, What Actually Makes Something Alive?

Maybe the problem is that we keep trying to find a single universal definition. Life is messy. It evolves. It adapts. It resists boxes.

At its core, perhaps life is not a thing but a process—a dynamic state of matter that resists entropy (disorder) through energy use, self-organization, and evolution.

That would mean life isn’t a yes/no category, but an ongoing struggle. Which, when you think about it, is exactly how it feels to be human.

Conclusion

Biology’s struggle to define life reveals more about us than about the universe. We crave neat categories, but nature often refuses to play along. Viruses, synthetic organisms, and possible alien life forms all blur the lines we once thought clear.

So, what makes something alive? Maybe the real answer is: life makes itself.

And perhaps our obsession with definitions says less about biology and more about our fear of ambiguity. After all, if we can’t define life precisely, what does that say about our own place in the cosmos?

Author’s Note

As I wrote this, I couldn’t help but notice how much biology’s struggle mirrors our own human struggle—to define, to label, to categorize. Maybe it’s time we admit that being alive is less about meeting criteria and more about existing in that fragile, beautiful state between order and chaos.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.