Fun fact: the world’s 74 lowest-income countries account for only about 10% of greenhouse gas emissions, yet they are among those hit hardest by climate disasters.

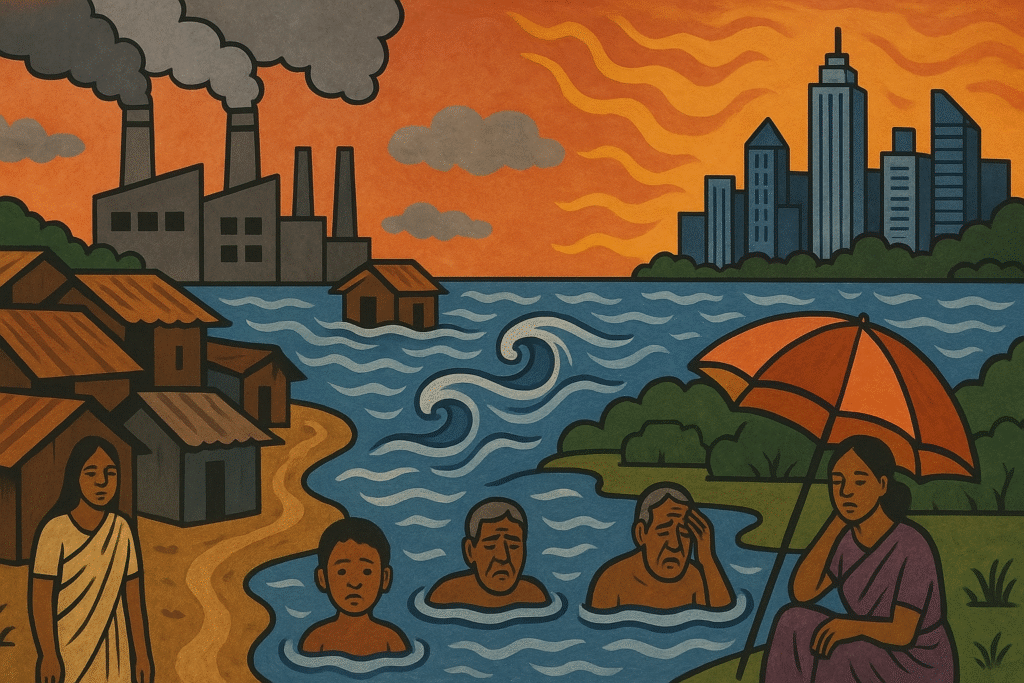

Environmental Justice: Who Bears the Brunt of Climate Change? seeks to dig into why the poorest and most vulnerable often suffer first and worst—and what that says about fairness, responsibility, and policy.

The Scale of Inequality in Climate Impacts

Globally, the burden of climate change is distributed very unequally. The countries with the fewest emissions are already experiencing many more disasters than before. They suffer droughts, floods, cyclones, heatwaves, sea-level rise—while having the least resources to adapt or recover.

Within nations, too, it tends to be poor people, marginalized groups (including racial or ethnic minorities, informal settlers, or slum dwellers), and those with weaker infrastructure who are most exposed. Their homes may be in flood plains, with weak building materials; they may lack reliable electricity, water, or healthcare; they have fewer financial reserves. All this makes even moderate climate shocks into crises.

Heatwaves in Slums and Cities: A Case Study

In many urban areas, slums amplify heatwaves. Consider low-income districts in big cities where housing is dense, windows are small or lacking, few trees, and there are lots of concrete and metal roofs: these become “heat islands.” Temperatures soar. At night, poorly insulated homes don’t cool down. People without access to cooling tools (like fans or air conditioners), or who must work outdoors, suffer the worst: heat exhaustion, dehydration, worsened chronic illness, even death.

A study from the United States shows how communities of colour and low-income neighbourhoods face greater exposure during heatwaves, linked in part to past policies like segregation or under-investment in green infrastructure. The same dynamic plays out globally—informal settlements in South Asia, Africa, and Latin America face similar risks but with far fewer safety nets.

Industrial Pollution and Marginalized Communities

It isn’t just climate disasters. Air and water pollution from industry often disproportionately affects poorer communities. Factories tend to be sited near areas with cheap land, weak regulation, or neighbourhoods without political clout. Those living nearby suffer more respiratory disease, contaminated water, and unsafe soil. Often, communities most directly exposed are those with the least ability to move, protest, or demand accountability.

For example, in Pakistan, which emits a very small share of global greenhouse gases, devastating floods in 2022 affected millions—destroying homes, crops, and infrastructure. Many poor people were displaced, losing both shelter and income. The health consequences—waterborne diseases, lack of clean water—hit hardest where infrastructure was weakest.

Why Vulnerability and Poverty Are Multipliers

Poverty multiplies climate risk in many ways:

Lack of adaptive capacity: No savings, no insurance, no resilient housing. Even a small loss can mean hunger, debt, or worse.

Geographical exposure: Poor people often live in high-risk zones—coastlines, floodplains, informal settlements, and low-lying areas.

Weak institutions: Limited access to government aid, emergency services, and health systems. Corruption or lack of trust can also block relief.

Preexisting social inequities: Gender, caste, race, ethnicity, and migrant status—all influence who gets more burden. Women often care for water, food, children, and the elderly; when droughts or floods occur, gendered burdens rise.

Ethical Dimensions & Why This Matters for All of Us

This is not just “other people’s problem.” There are ethical, economic, and moral dimensions:

Ethics: Do we accept that some people suffer because of emissions they did not cause?

Stability: Disasters displace people, create refugees, destabilize societies, and exacerbate inequality. Everyone is affected by instability.

Health: Diseases, food insecurity, and water shortages spread beyond borders.

Economic costs: When disasters strike, even wealthy countries pay—through global supply chains, migration, insurance, and trade disruptions.

What Equitable Climate Action Looks Like

To make climate action just, here are some approaches:

- Prioritize adaptation funding for vulnerable countries and communities (slums, indigenous people, marginalized castes).

- Incorporate justice into policy design: cooling centres, tree cover, resilient housing, and health services in vulnerable areas.

- International financial support and debt relief for the poorest nations to invest in adaptation.

- Include vulnerable voices in planning and decision-making—local communities often know best what works.

- Make emissions cuts in rich countries steeper, faster: those with the biggest historical and per capita emissions carry more responsibility.

Conclusion

Climate change isn’t just an environmental issue—it’s a question of justice. The world’s poorest people, those who contribute least to the problem, carry the heaviest burdens. If we want a fair future, we must not let “victim of geography or poverty” become a fate we accept.

Author’s Note

I wrote this because too often I see climate debates dominated by percentages, emissions targets, and tech fixes—and not enough about who already pays the cost. The poor deserve more than sympathy; they deserve fairness, voice, and action.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- World Economic Forum: The climate crisis disproportionately hits the poor — how low-income countries emit little yet suffer greatly.

- Low-Income Communities Bear the Brunt of Climate Change (Earth.org) — examples including Pakistan floods, food, and water crises.

- Heat Waves Amplify Existing Inequities – UC San Diego study — how marginalized communities in hot cities face more heat stress.

- Climate Justice and Urban Heat Inequity (MDPI) — literature review of thermal inequity in low-income urban communities.

- Global CO₂ Emissions Inequality (Our World in Data) — how low-income countries emit far less than wealthy ones.

- Environmental Justice and Climate Change Policies (PMC) — analysis of how low-income populations suffer and what policy fairness demands.

Comments

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to come back in the future. Cheers