Fun Fact: In March 2020, a single choir rehearsal in Washington state turned into one of the most important case studies for understanding how COVID-19 spreads, long before the World Health Organisation (WHO) officially acknowledged the virus was airborne.

Introduction: When One Voice Changed the Air

The year was 2020. The world was just beginning to come to terms with a mysterious virus making headlines—COVID-19. Governments scrambled, masks were debated, and public health advice was inconsistent. Amid all this confusion, a choir group in Mount Vernon, Washington—a small town in the Pacific Northwest—gathered for their regular rehearsal.

They followed every public health guideline in place at the time. No one had symptoms. No one hugged or shook hands. Yet, within a few days, 52 out of 61 singers fell ill. Two of them died.

This wasn’t just a tragic superspreader event—it became a scientific turning point. The story of the Skagit Valley Chorale helped scientists prove what many had suspected but were struggling to confirm: COVID-19 spreads through the air.

This blog dives into how that one evening rewrote the rulebook on disease transmission, changed scientific consensus, and continues to shape how we think about air, health, and public spaces.

The Event That Sang a Warning

On March 10, 2020, 61 members of the Skagit Valley Chorale assembled for a 2.5-hour rehearsal. They practised with discipline, avoided physical contact, and used hand sanitisers. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had not yet recommended masks, and COVID-19 wasn’t believed to be widespread in the area.

Yet, within days:

- 53 members tested positive or had symptoms

- 3 were hospitalised

- 2 tragically passed away

There was no buffet. No close mingling. The only shared factor? Air.

Researchers were baffled if COVID-19 could spread like this—just by breathing and singing—then the basic assumptions about transmission needed to be urgently revisited.

Challenging the Consensus: Is COVID Really Airborne?

At the time, WHO and other health agencies clung to a surface-based (fomite) and droplet model of transmission. This meant people were told to wash their hands frequently, clean surfaces, and stay six feet apart. Ventilation was hardly mentioned. Masks were optional or discouraged.

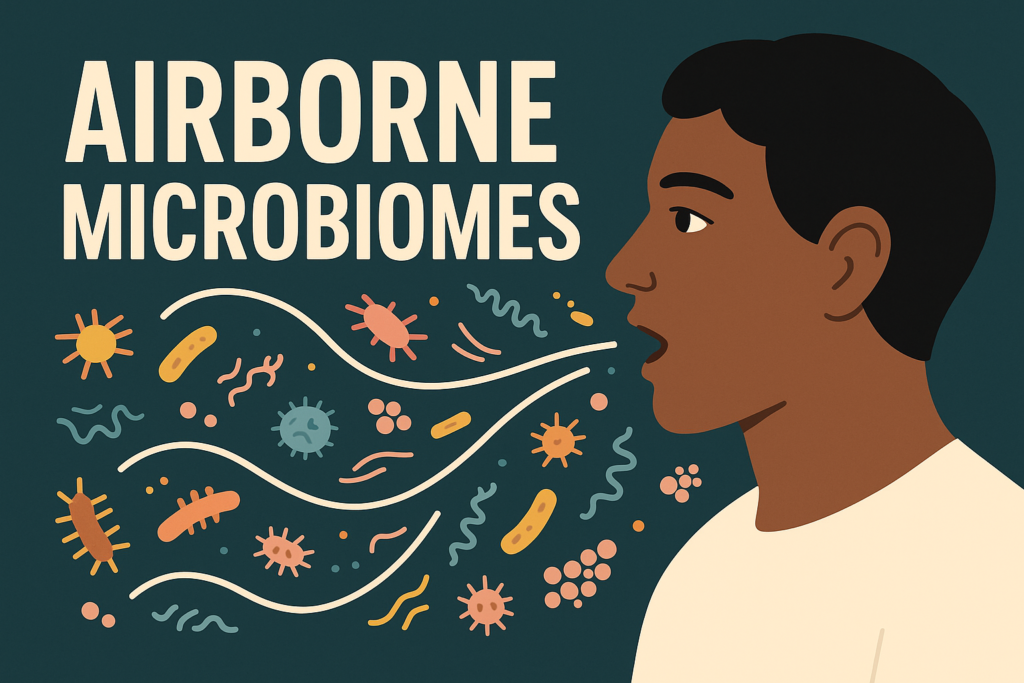

But a small group of scientists—including Dr. Donald Milton at the University of Maryland and Lindsay Marr, an expert in airborne particles—had been warning that respiratory viruses, especially COVID-19, might behave more like smoke than spit.

The Skagit Valley case supported that view. It became Exhibit A in the global argument that aerosols—microscopic respiratory droplets that linger in the air—could carry the virus far beyond six feet.

Aerobiology: The Science We Forgot

The study of airborne life, known as aerobiology, is not new. In the 1930s, scientists like William and Mildred Wells demonstrated that diseases such as measles and tuberculosis could be transmitted through the air. Their work showed that ultraviolet (UV) light could kill pathogens in airborne droplets, making enclosed spaces safer.

But despite this, public health bodies had largely abandoned aerobiology. Instead, the focus shifted to germs on hands, surfaces, and coughs. Air was considered “clean” by default.

Zimmer’s recent book Airborne reveals how decades of scientific progress in aerobiology were lost due to egos, institutional resistance, and even classified military research.

The COVID choir event resurrected that lost knowledge.

Why the Choir Case Mattered So Much

The Skagit Valley outbreak was important because:

- It was well-documented: The participants gave detailed accounts, enabling scientists to map seating arrangements, exposure time, and ventilation conditions.

- It lacked confounding variables: No food, minimal physical contact, and no symptomatic individuals, ruling out other transmission routes.

- It was symbolic: Singing, an activity tied to joy and community, became the perfect metaphor for the invisible threat.

A peer-reviewed study published in Indoor Air (2021) modelled the event using physics and aerosol science. It concluded that aerosol transmission—not droplets, not surfaces—was the primary route.

This pushed agencies like the WHO to revise their stance in 2021, acknowledging COVID-19 as an airborne disease.

How History Repeats Itself

Ironically, the Wellses had faced similar resistance in the 1930s and ’40s when trying to convince the medical establishment that measles and tuberculosis spread through the air. Their work was ignored by peers but embraced—secretly—by the U.S. military, which used it to develop bioweapons during WWII and the Cold War.

That dark legacy meant decades of aerobiological data were classified, stalling public health research. The choir case reignited the conversation and reminded us how much we had forgotten.

What We’ve Learned—and Still Ignore

Today, we know:

- Ventilation matters as much as vaccination

- Masks work, especially N95 or better

- CO₂ monitors are useful proxies for indoor air safety

- UV-C light and air filtration can dramatically reduce infection risks indoors

Yet, progress is slow:

- Most countries have no air quality mandates for infectious disease prevention.

- The U.S. government published indoor air guidelines in 2021, but they were taken down in 2024.

- Schools, offices, and public buildings remain poorly ventilated in many parts of the world.

Belgium is one of the few countries moving toward legal standards for air quality in public spaces.

The Human Cost of Delay

If agencies had acted earlier—acknowledging airborne transmission—millions of lives might have been spared. Schools, hospitals, and nursing homes could have been retrofitted with UV, HEPA filters, and better ventilation systems.

Instead, for much of the pandemic, people were scrubbing surfaces while ignoring the very air they breathed.

The choir story is a haunting reminder that public health depends not just on good data, but on the courage to challenge outdated beliefs.

Conclusion: Let the Choirs Be Heard

The Skagit Valley Chorale didn’t set out to make history. They just wanted to sing. But in doing so, they taught the world a vital lesson: airborne diseases demand airborne solutions.

Their story—once tragic and forgotten—has become part of the scientific record, cited in countless studies, used in university lectures, and featured in books like Airborne by Carl Zimmer.

As we face future pandemics, their voices remind us: Pay attention to the air. It’s not empty. It’s alive.

Author’s Note

I wrote this blog with deep respect for the Skagit Valley Chorale and the scientists who fought to bring airborne transmission to light. The air we share connects us, and protecting it protects everyone. Let’s not wait for the next pandemic to learn the same lesson again.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- The Skagit Valley Choir Outbreak – CDC

- Zimmer, Carl. Airborne: The Hidden History of the Life We Breathe

- Indoor Air Journal Study (2021)

- Team, C. E. (2003). Source of US monkeypox outbreak of identified, and CDC issues updated interim guidance for prevention and treatment of monkeypox. Weekly Releases (1997–2007). https://doi.org/10.2807/esw.07.27.02251-en