Did you know there may be more fresh water hidden beneath the ocean floor than in all the world’s rivers combined?

Yes, you read that right. While we argue over droughts, dam projects, and desalination plants, scientists have quietly discovered something extraordinary: secret aquifers of fresh water locked beneath the seabed, stretching for hundreds of kilometres along coasts. In this blog, “Secret Freshwater Oceans: Tapping Earth’s Hidden Reservoirs”, we’ll explore what this means for a thirsty planet—and why it might be both a lifeline and a dangerous temptation.

The Discovery: A Hidden Ocean Beneath the Ocean

Back in 2019, researchers using electromagnetic imaging—a technology that detects differences in salinity (saltiness)—mapped vast underground reserves of low-salinity water beneath the seabed. Think of it like groundwater, but trapped offshore, under layers of sand, silt, and clay.

The largest confirmed reservoirs stretch from New Jersey to Massachusetts in the United States, but signs of similar aquifers exist off Australia, South Africa, China, and Hawai‘i. The global volume? A staggering 1 million cubic kilometres. To put that in perspective, it’s more than 100 times the volume of Lake Superior, the largest freshwater lake in the world.

Where Did All This Water Come From?

Scientists believe these offshore aquifers have multiple origins:

Ice Age Legacy: During the last glacial period, sea levels were much lower. Rivers and rainwater seeped into the ground, filling porous sediments that are now submerged. When the seas rose, clay and silt sealed those aquifers like Tupperware lids.

Modern Recharge: In some regions, freshwater continues to flow offshore through permeable rock, recharged by rainfall or rivers inland. Hawai‘i, with its volcanic basalt layers, is a perfect example.

Confined Aquifers: Natural “caps” of clay keep seawater from mixing with these precious reserves, preserving their drinkability.

It’s as though nature left us time capsules of fresh water, waiting to be found.

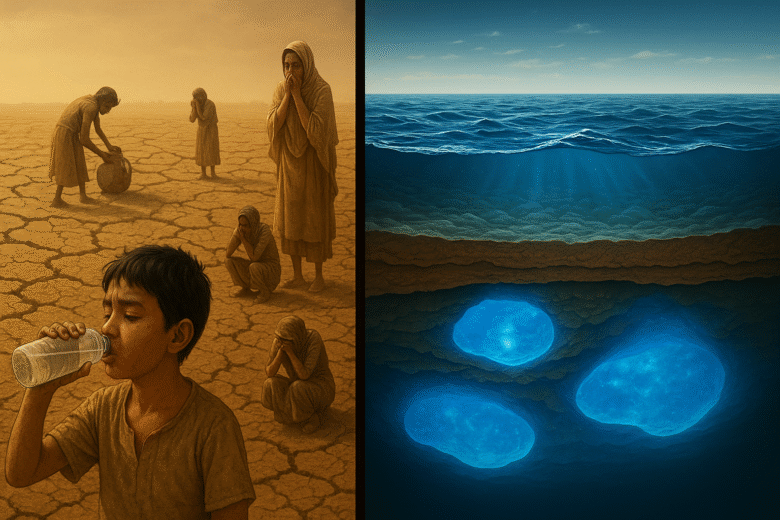

Why This Matters: A Thirsty World

Fresh water is running out. According to the United Nations (UN), over 2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, and climate change is making droughts more frequent. India knows this pain well—remember Chennai’s “Day Zero” in 2019, when the city’s reservoirs went bone dry?

Offshore aquifers could be a game-changer:

- Island nations like the Maldives or Pacific archipelagos could reduce dependence on expensive desalination plants.

- Coastal megacities such as Mumbai, Cape Town, or Jakarta could tap these resources during crises.

- It could buy humanity time while we fix water management and adapt to climate extremes.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: tapping these resources may save us today, but doom us tomorrow if we exploit them recklessly.

The Catch: Challenges and Risks

Extracting fresh water from under the sea isn’t as simple as digging a well in your backyard.

Cost: Offshore drilling and pumping would require oil-rig-level infrastructure. Imagine water priced like petroleum.

Saltwater Intrusion: Pump too aggressively, and seawater will flood in, contaminating the aquifer.

Sustainability: If the water is mostly “fossil” (from the Ice Age), it’s non-renewable. Once gone, it won’t come back for thousands of years.

Ecological Risks: Messing with undersea geology could disturb fragile ecosystems we barely understand.

Ownership Battles: Who owns offshore groundwater? The country whose coastline it lies under? Or should it be considered a global resource, like the high seas? International law hasn’t caught up yet.

It’s a Pandora’s box of opportunity and peril.

Case Studies and Research Highlights

New England, USA: Drilling expeditions confirmed nearly fresh water trapped 400 meters below the seabed, with salinity levels close to drinkable.

Pearl River Estuary, China: A 2023 study found offshore reservoirs extending far into the shelf, offering new hope for southern China’s water-stressed regions.

Hawai‘i: Advanced imaging revealed freshwater moving offshore in volcanic layers—a discovery that challenges traditional water cycle models.

These aren’t science-fiction stories. They’re happening right now.

The Provocative Question: Should We Use It?

Here’s where opinion divides. Some argue it’s irresponsible to even think of drilling into these aquifers—like robbing a bank to pay today’s bills. Others argue that not using it while people die of thirst is equally immoral.

Personally? I think it’s dangerous to put blind faith in any “hidden resource.” History teaches us that every time humanity finds a new treasure—oil, coal, fish stocks—we rush to exploit it, only to regret it later. Offshore freshwater should be our emergency reserve, not our everyday tap.

Instead of chasing hidden aquifers, why not:

- Fix leaking municipal pipes (India loses nearly 40% of piped water to leaks).

- Harvest rainwater more aggressively.

- Treat and reuse wastewater.

- Protect rivers and wetlands from industrial abuse.

Offshore aquifers might be the ace up our sleeve—but should we really play it unless we have no other choice?

Conclusion

The discovery of offshore freshwater aquifers is a thrilling reminder that Earth still holds secrets. These hidden reservoirs could save millions in times of crisis, but they also tempt us toward short-term fixes at the expense of long-term survival.

The real challenge isn’t finding water—it’s learning to respect it. If we can’t manage the lakes, rivers, and aquifers we already have, do we really deserve the oceans’ hidden gift?

Next time you let a tap run unnecessarily, remember: beneath the waves, a secret ocean of fresh water waits. But perhaps it’s best left untouched—until we’ve learned to value the water in our hands.

Author’s Note

As someone who grew up in a water-scarce city, I find this discovery both hopeful and troubling. It excites me to imagine hidden lifelines beneath the sea, but it scares me even more to think we’ll repeat the mistakes we made with fossil fuels. I believe the greatest innovation we need isn’t new technology—it’s a new attitude toward conservation.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

Comments

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me & my neighbor were just preparing to do a little research on this. We got a grab a book from our area library but I think I learned more from this post. I’m very glad to see such fantastic information being shared freely out there.