Fun fact: it takes almost 1.9 million litres of water to produce just one tonne of lithium — enough water to fill nearly 760 average bathtubs!

Welcome to The Green Energy Paradox, where our dream of clean solar panels, wind turbines, and electric cars hides a darker, messy reality. We need these technologies for a clean future — but producing them demands huge amounts of critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, nickel and more. And that means more mining, which raises tough questions about biodiversity loss, supply chain ethics, and what it really means for clean tech to be green.

Why Clean Tech Needs Dirty Minerals

The renewable energy transition leans heavily on certain minerals. Electric vehicle (EV) batteries, solar photovoltaics (PV) panels, and wind turbines all require metals like lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, and rare earth elements. For example:

- Lithium is essential for most lithium-ion batteries powering EVs and grid storage.

- Cobalt stabilizes those batteries but often comes with severe social and environmental baggage.

- Nickel adds energy density, but its mining brings its own environmental and health issues.

The demand for these materials is set to explode as countries double down on climate goals. Extraction is energy-intensive, water-hungry, and often requires large scale land-use changes. We trade fossil fuel carbon emissions for damage to ecosystems, water supplies, and human communities.

Biodiversity Under Siege

Mining often removes vegetation, alters landscapes, and disrupts habitats. In drier regions where lithium-rich brine deposits lie, water use for extraction can be enormous, drying up salt lakes, reducing groundwater, and threatening plants and animals unique to those areas. One of the largest proposed lithium mines, Thacker Pass in Nevada, is located in a corridor used by pronghorn antelope and mule deer. Wildlife experts have raised alarm over its adverse impacts to both ground and surface waters and riparian vegetation, and called out how some species might lose breeding grounds permanently.

In agricultural or forested regions, mining operations fragment soil, cut waterways, and threaten livelihoods. Communities near proposed or operating lithium or rare earth mines worry about loss of soil fertility, polluting run-off, and forest destruction, even when the sites are meant to power clean tech elsewhere.

Water, Pollution, and Health

Even “clean” energy minerals create dirty problems. Mining via salt flats or brines uses massive volumes of water and often chemical additives; hard rock mining generates tailings that may contain toxic by-products. In places like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), cobalt mining has been linked to soil erosion, water pollution, and serious health issues for people living nearby. In the region around Kolwezi, many report increases in birth defects, stillbirths, and waterborne health problems, tracing them back to polluted water sources affected by mining operations.

In Thacker Pass, concerns about groundwater depletion and contamination are strong. Ranchers and farmers in nearby areas worry about wells drying up or becoming unsafe. Environmental reports for that mine note that assumptions made in water rights and recharge may have been overly optimistic, and that effects to surface and groundwater quality need more scrutiny.

Ethical (and Unethical) Supply Chains

People aren’t abstract in this story — there are human lives in this equation. In the cobalt belt of the DRC, child labour, unsafe working conditions, and inadequate health protection have been repeatedly documented among miners. Women report increased risks to reproductive health, including miscarriages and birth defects, due to toxic exposures.

Indigenous communities near Thacker Pass assert that their ancestral lands are threatened and that they were not properly consulted. Land that they consider sacred or vital for their way of life risks being taken over or degraded without fair compensation or meaningful consent.

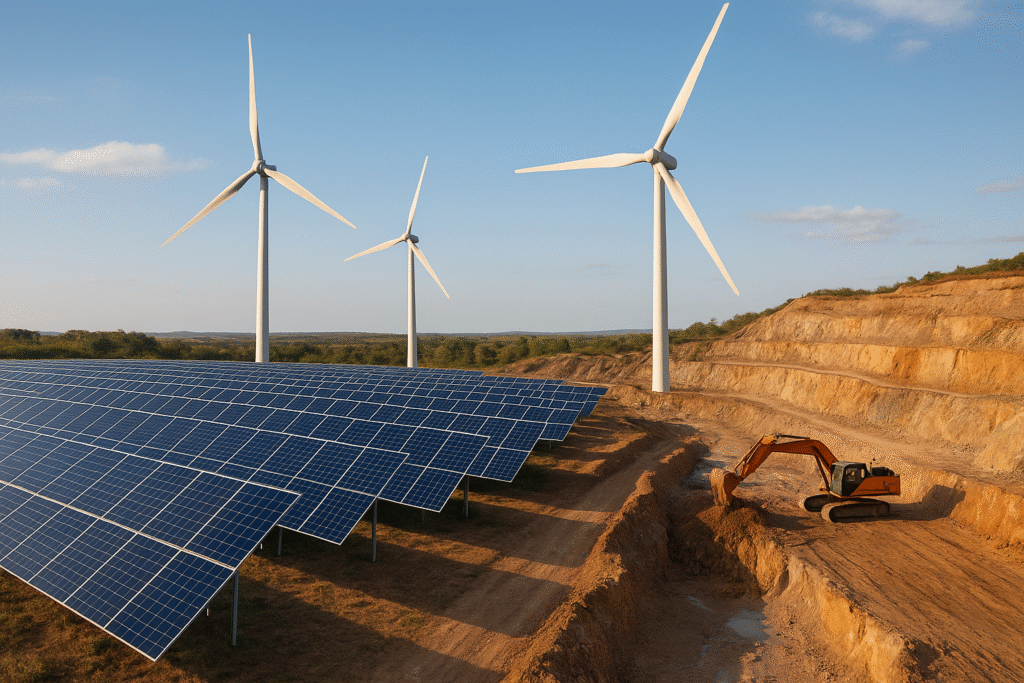

Renewable Infrastructure’s Own Footprint

Just because solar panels or wind turbines don’t emit carbon during operation doesn’t mean they are impact-free. Building them requires mining silicon, copper, silver, rare earths; installing them uses land, sometimes displacing habitats; and end-of-life disposal or recycling is often underprepared for. Wind turbines can affect birds and bats, and solar farms sometimes replace natural vegetation, harming local ecosystems. Blades and panels discarded without planning add to waste burdens.

The Demand Balloon: Can We Meet It Responsibly?

If every country targets net-zero emissions by mid-century, demand for copper, lithium, cobalt and related materials could multiply by several times. While recycling, reuse, and innovation (such as batteries with less or no cobalt) help, they are unlikely to eliminate the need for new mining entirely.

Some better practices are emerging — governments and NGOs pushing for responsible sourcing standards, efforts to ensure free, prior, informed consent from affected communities, design for reuse, restoration of mined lands, and more rigorous environmental impact assessments.

Trade-Offs, Not All Doom

It’s crucial to compare: the environmental cost of material mining is serious but often still less destructive than continuing fossil fuel production unchecked. Clean technologies reduce air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, acid rain, ocean acidification. Clean tech isn’t the villain; the way we source, build, deploy, and retire it determines whether it’s truly a force for good.

Conclusion

The Green Energy Paradox reminds us that “green” is not automatically “good.” Solar panels, wind turbines, and electric cars are essential tools in fighting climate change — but they carry hidden environmental and ethical costs in their raw materials and supply chains. If we ignore these, a new kind of damage may follow us, even as we reduce carbon emissions.

We must demand more: stricter regulation of mining practices, meaningful inclusion of affected communities, protection of biodiversity, investment in recycling and sustainable materials, and transparency in supply chains. Governments, companies, and the public all share this responsibility.

Author’s Note

I wrote this because I often hear renewables praised as a moral silver bullet. They are vital — but they are not without cost. Someone needs to hold up the mirror, because real sustainability demands honesty, not just hopeful slogans.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- Earth.Org: The Environmental Impacts of Lithium and Cobalt Mining

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health: The Dangers of Cobalt Mining in the Congo

- Protect Thacker Pass: Fact Sheet about Proposed Thacker Pass Mine Project

- New Report Finds Nevada’s Lithium Mine Permit Violates Indigenous Peoples’ Rights

- Questions Over Water Rights Could Halt Construction at Thacker Pass Lithium Mine

- Mongabay: Cobalt Mining for Green Energy Risks Women’s Reproductive Health in DRC

- The Guardian: Rise in Women With Reproductive Health Issues Near DRC Cobalt Mines

- Forced Labor in Cobalt Mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo

- The Kings River pyrg Snail and Threats from Lithium Mining

Comments

Valuable info. Fortunate me I found your website by chance, and I am shocked why this twist of fate didn’t happened earlier! I bookmarked it.