Fun fact: Some of the largest structures in the universe are completely invisible—until you tune in to radio waves.

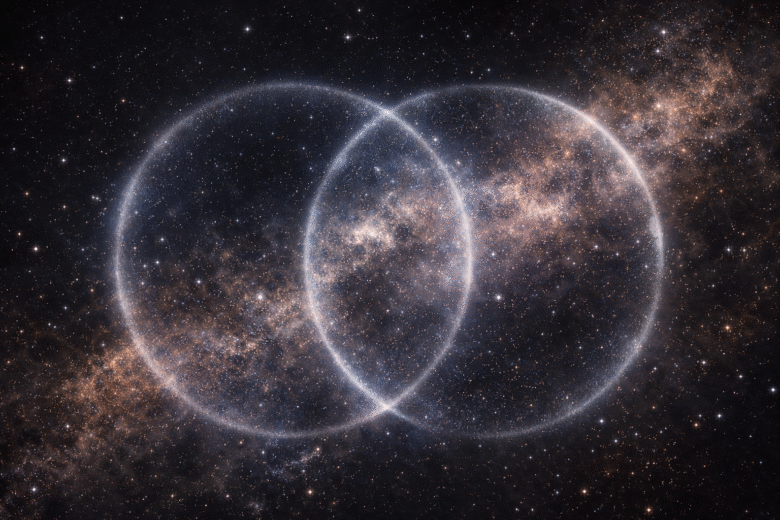

That unsettling idea sits at the centre of The Universe Just Drew a Circle We Can’t Explain, a story that feels less like a discovery and more like a quiet provocation. Astronomers have detected the most powerful and distant odd radio circle, a vast ring of energy floating billions of light-years away, glowing only in radio frequencies. No stars outline it. No galaxies neatly fill it. It is simply there—immense, ancient, and stubbornly unexplained.

In an age where space discoveries often arrive pre-packaged with confident explanations, this one does something rarer. It admits uncertainty.

A Circle That Shouldn’t Exist

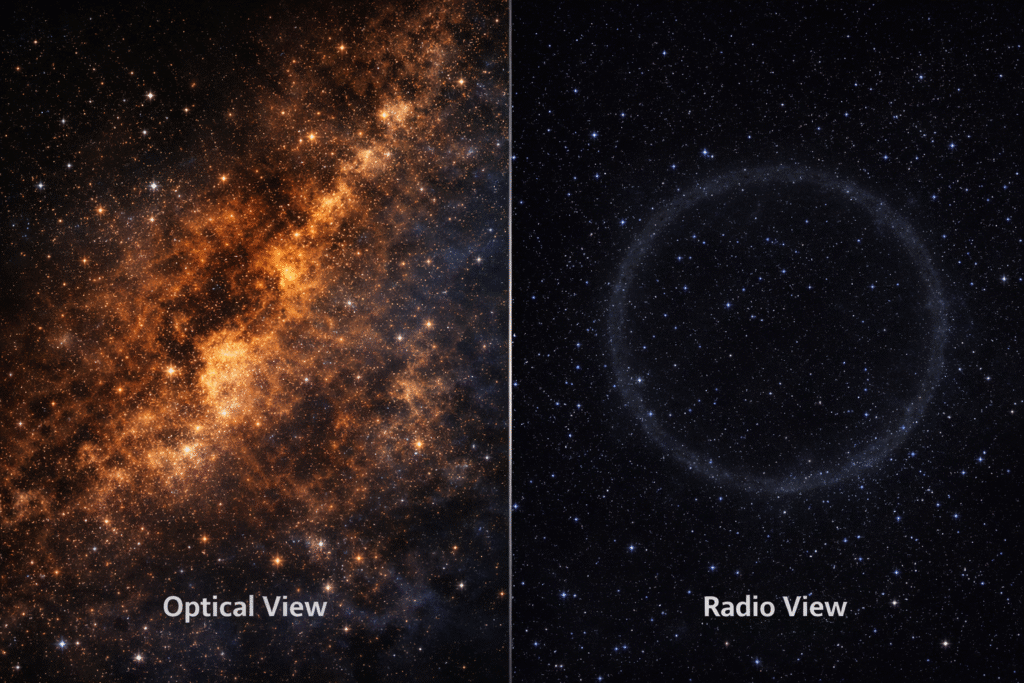

Odd radio circles—often shortened to odd radio circles (ORCs)—are among the strangest structures ever spotted in the cosmos. They appear as enormous, faint rings in radio telescope images, sometimes stretching millions of light-years across. Look for them with ordinary telescopes and you see nothing. No glow. No dust. No familiar celestial landmarks.

This newly detected ORC is different even by these strange standards. It is the most distant and most powerful of its kind ever observed, formed when the universe was far younger than it is today. The radio signal reaching Earth has travelled for billions of years, carrying with it a message from a time when galaxies were still learning how to grow old.

What makes it more unsettling is its shape. Instead of a single neat ring, astronomers observed overlapping circles, like ripples colliding on the surface of a cosmic pond. This is not geometry we are comfortable with. It does not fit easily into existing theories.

And that discomfort matters.

Why Radio Waves Change the Story

Most of what we know about space comes from light we can see—or at least detect indirectly. Radio astronomy rewrites that relationship. It listens instead of looks.

Radio waves reveal energetic processes that optical light often misses: charged particles racing through magnetic fields, shockwaves rippling through space, ancient outbursts that have long faded in other wavelengths. ORCs exist almost entirely in this hidden radio universe.

That means they are not decorative objects. They are events frozen into structure—the aftermath of something powerful that happened long ago.

The problem is that astronomers do not yet agree on what that something was.

Theories, None Comfortable

Several explanations compete to make sense of odd radio circles, and none fully satisfy.

One idea suggests they are shockwaves from violent galactic events—perhaps collisions between galaxies or sudden eruptions from supermassive black holes at their centres. Another possibility is that they are the radio echoes of enormous jets blasting into surrounding space, expanding outward until they form ring-like shells.

But the newly discovered ORC complicates these ideas. Its sheer power, distance, and double-ring structure stretch every model. If these circles were rare accidents, why are we now finding them at such vast scales? And if they are common, why did we miss them for so long?

The uncomfortable answer is that our instruments were simply not listening carefully enough.

When Humans Still Matter in Big Data

One of the quieter but more hopeful details in this discovery is how it was found. Amid oceans of data generated by modern radio telescopes, human eyes still played a role. Citizen scientists—trained volunteers scanning images for anomalies—helped flag the unusual circular pattern that machines might have dismissed as noise.

In an era obsessed with automation, ORCs remind us that curiosity still has a human shape. Sometimes, discovery begins not with certainty, but with someone pausing and saying, “That looks strange.”

It is a comforting thought: even as our tools grow vast, attention still matters.

A Young Universe Doing Wild Things

Perhaps the most profound aspect of this ORC is its age. Because it lies billions of light-years away, we are seeing it as it existed when the universe itself was younger, more chaotic, and less settled into predictable patterns.

This raises an unsettling possibility: odd radio circles may not be odd at all. They may be common features of an energetic early universe—cosmic scars left behind by processes we no longer witness as frequently nearby.

If that is true, then ORCs are not anomalies. They are memories.

And the universe, it seems, has a very long memory.

Why This Matters Beyond Astronomy

It is tempting to treat this as an abstract curiosity, far removed from life on Earth. But there is a deeper lesson here.

We live in a time where explanations are expected instantly. News cycles demand closure. Science communication often rushes to reassure. ORCs resist that impulse. They exist without apology, reminding us that knowledge is always provisional.

There is something healthy about that reminder.

When the universe draws a perfect circle and refuses to tell us why, it teaches humility. It reminds us that understanding is not a destination but a practice—one that requires patience, doubt, and the willingness to sit with mystery.

Conclusion: Learning to Sit With the Unknown

The most powerful and distant odd radio circle ever seen does not threaten us, inspire fear, or promise utility. What it offers instead is rarer: intellectual unease.

It asks us to accept that even now—after centuries of observation and decades of space exploration—the universe still produces structures we cannot easily explain. And perhaps that is not a failure of science, but its quiet triumph.

If we want to understand the cosmos, we must first learn to listen without demanding answers on our schedule.

The circle is there. The meaning will take time.

Author’s Note

This discovery stayed with me because it refuses resolution. A vast circle, formed long before Earth learned to name the stars, still sending a signal we barely understand—it feels like a lesson in patience written across the sky. In a world rushing toward conclusions, this story asks us to slow down and look again.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.