Fun fact: In 1966, a simple chatbot named ELIZA fooled people into thinking it understood them—just by rephrasing their words into questions. That was nearly 60 years ago, yet here we are in 2025 still asking: Do machines really “understand”?

The Turing Test and Its Successors: Can Machines Really ‘Understand’? remains one of the most provocative questions in technology. When British mathematician Alan Turing—often called the father of computer science—proposed his now-famous “Imitation Game” in 1950, he asked a simple but unsettling question: If a machine can convincingly imitate a human in conversation, should we say it thinks?

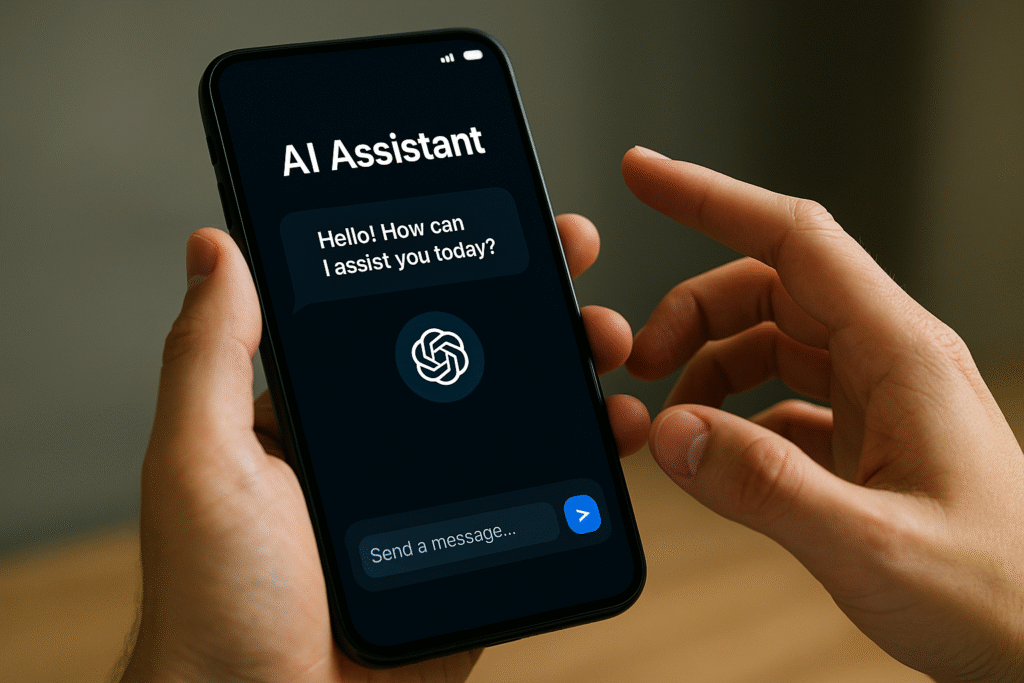

Today, as we chat with Siri (Apple’s digital assistant), ask Alexa (Amazon’s smart speaker service) to play music, or draft essays with ChatGPT (a conversational AI made by OpenAI, a U.S.-based AI research company), Turing’s question hits closer to home than ever.

But here’s the twist: Just because a machine sounds human doesn’t mean it is.

The Turing Test: A Game of Pretend

Turing’s original test wasn’t about whether a computer “understood” anything. It was about performance. Could a machine trick a human judge into believing they were conversing with another person? If yes, Turing argued, that was enough evidence to call it “intelligent.”

Sidebar: What Was the “Imitation Game”?

When Alan Turing first introduced what we now call the Turing Test, he described it as the “Imitation Game.”

- Originally, it involved three players: a man, a woman, and a human judge.

- The judge asked written questions to figure out which was which.

- Turing then suggested swapping one player with a machine.

- If the judge couldn’t reliably tell the machine from the human, the machine had effectively “passed” the game.

In short: the Imitation Game was Turing’s way of testing if machines could convincingly “act human.” Today, we simply call it the Turing Test.

Think of it like a parrot saying “Hello.” Charming? Yes. Conscious? Not really.

Why the Turing Test Fell Short

The Turing Test was groundbreaking but flawed:

- Shallow Tricks Work Too Well

Machines don’t need deep understanding—just clever misdirection. ELIZA survived by asking vague, therapist-like questions. - Humans Are Too Easy to Fool

We anthropomorphize everything. From naming our cars to yelling at Alexa, humans tend to project intelligence where none exists. - It Doesn’t Measure Real Understanding

A calculator crunches numbers in seconds that would take you minutes—or hours. Does that mean it “understands” algebra? Hardly.

This is where philosophers like John Searle weighed in with his Chinese Room Argument (an idea experiment from 1980). He imagined a man in a room who follows a rulebook to manipulate Chinese symbols but doesn’t speak Chinese. Outsiders might think he understands—but inside, he’s just shuffling symbols. Searle’s point: computation isn’t comprehension.

Successors to the Turing Test

The debate didn’t stop there. Over the years, scientists and engineers have tried to create more robust tests of machine intelligence:

- Winograd Schema Challenge (2011)

A test designed by Hector Levesque, where an AI must resolve pronoun references in tricky sentences.

Example: “The city councilmen refused the demonstrators a permit because they feared violence.” Who feared violence? Humans easily know it’s the councilmen. Machines often fail. - The Coffee Test (by Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple)

If an AI can walk into a random kitchen and make a cup of coffee, then it has “general intelligence.” So far, no robot has passed. - The Lovelace Test (2001)

Named after Ada Lovelace, the first computer programmer. The idea: Can an AI create something novel that its programmers can’t explain? Creative art, original music, or truly surprising writing. - Ethical and Social Tests

Some argue real intelligence should include moral reasoning. Can AI weigh right from wrong? Can it decide not to follow harmful instructions?

These tests highlight one thing: passing the Turing Test is no longer impressive. We demand more.

The Modern Era: ChatGPT, Bard, and Gemini

Today’s chatbots—like ChatGPT (by OpenAI), Gemini (Google’s AI assistant by Alphabet Inc., a U.S.-based technology giant), and Claude (by Anthropic, a San Francisco-based AI safety company)—can write poetry, summarize legal cases, and even crack jokes. They pass casual conversation tests with flying colours.

But here’s the uncomfortable question: Do they understand what they’re saying?

When ChatGPT explains Shakespeare, is it channelling understanding—or just remixing patterns from billions of texts? When Gemini suggests a restaurant, does it know what hunger feels like?

The gap between performance and awareness is glaring. These systems are masters of mimicry but novices of meaning.

The Public’s Confusion

And yet, many people are convinced machines “get it.” Why?

- Emotional Projection

When your voice assistant says, “I’m sorry, I didn’t understand that,” it feels like it has feelings. It doesn’t. - Speed and Fluency

Machines reply instantly. Humans confuse fluency with intelligence. - Hollywood Conditioning

From Ex Machina to Her, we’ve been primed to believe machines will eventually become sentient companions.

This gap between perception and reality is dangerous. Over-trusting machines in areas like healthcare, education, or justice can lead to catastrophic consequences.

So, Can Machines Really ‘Understand’?

Here’s the hard truth: Not yet.

Machines simulate understanding but lack consciousness, embodiment, or lived experience. They don’t know joy, hunger, or heartbreak. They don’t mean anything they say.

But—and here’s the provocative bit—maybe that doesn’t matter. If machines can collaborate, create, and solve problems alongside humans, maybe “understanding” isn’t the goal. Maybe usefulness is.

Still, we must be careful. Declaring machines “understanding” risks blurring lines between tool and being, between assistant and authority.

Conclusion

The Turing Test was the spark. Its successors—the Winograd schemas, Lovelace tests, and coffee challenges—show how high the bar really is. Machines today excel at imitation, but understanding is still a human monopoly.

So next time you’re tempted to ask Siri if she loves you back, remember: machines don’t understand us. They reflect us. And maybe that’s the most unsettling mirror of all.

Final thought: Before we grant machines the crown of “understanding,” let’s ask whether we truly understand what we’re building—and what it will mean for our future.

Author’s Note

As someone who straddles the worlds of education and technology, I believe we must keep questioning—not just what machines can do, but what they should. The Turing Test may no longer define AI, but the human responsibility to guide it has never been more urgent.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.