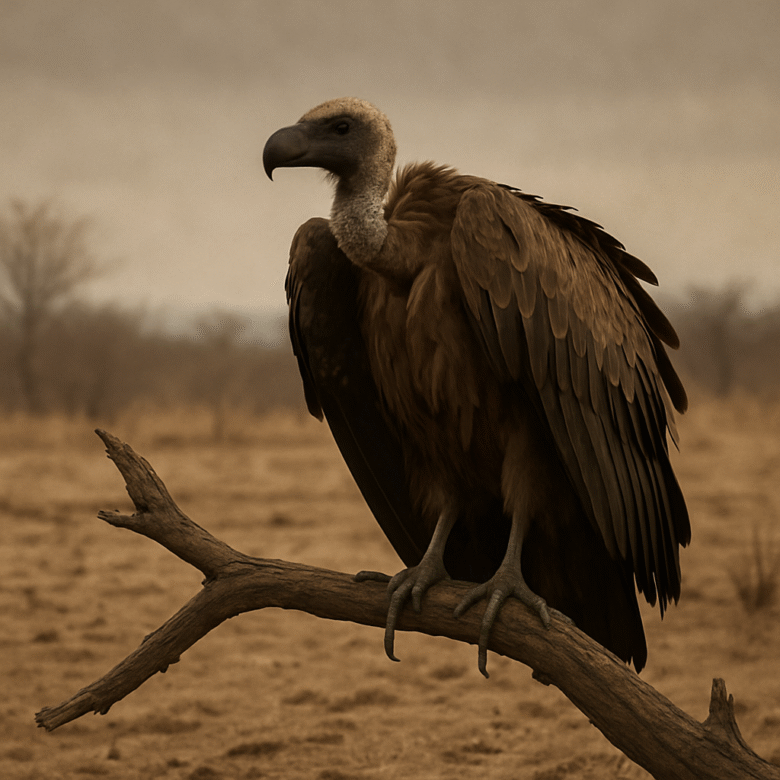

Fun fact: At one point, India’s vultures cleaned up more carcasses each year than the population of several small nations.

In “The Vulture Catastrophe”, we confront the tragic irony: a drug meant to heal cattle instead poisoned one of India’s most vital clean-up crews. The vultures vanished. In their absence, hidden threats lurked, diseases rose, traditions faltered, and we were forced to stare at how delicate the web really is.

This is not just a loss of birds. It is a collapse in sanitation, in ecological logic, in justice. In this post, I trace the downfall, the cascading fallout, and the urgent work of rebuilding that balance.

The Hidden Assassin: Diclofenac and the Death of Vultures

Claim: The veterinary painkiller diclofenac became a lethal poison for vultures, a tragedy born of blind spots and regulatory failure.

When farmers adopted diclofenac to treat cattle, it seemed a modest benefit: reduce suffering, improve livestock health. But vultures that fed on carcasses of cattle treated with diclofenac died of kidney failure and visceral gout. Postmortem studies revealed residues of diclofenac in a high proportion of dead vultures.

The decline was rapid and severe—the reduction exceeded 95 percent in Gyps vultures across affected zones.

The crisis escalated while institutions lagged: for years, the veterinary use of diclofenac continued with minimal oversight, despite clear links to vulture mortality.

Collapse in the Skies: What Disappeared Along with the Vultures

Claim: With vultures gone, a natural sanitation system collapsed—and its functions could not be replaced easily.

Vultures served as nature’s rapid carcass disposers. Their powerful stomach acids neutralized pathogens, their appetite reduced lingering decay, and their speed suppressed disease vectors.

Once vultures fell, carcasses lay exposed longer. Bacteria multiplied. Other scavengers—feral dogs, rats—moved in, less efficient and more dangerous.

The human health toll grew. Researchers estimated that between 2000 and 2005, as vulture populations collapsed, up to 100,000 additional human deaths per year were linked to the ecological gap left behind, totalling roughly half a million deaths over several years.

Economic burdens also surged: costs associated with carcass disposal, medical treatment, livestock loss, waste management—all amplified.

Culturally, traditions faltered. In Parsi communities, vultures once consumed corpses in “towers of silence.” As the birds vanished, corpses lingered; rituals could not proceed.

The vultures’ absence exposed how deeply our lives had come to depend on their silent service.

Who Fell First: Margins, Oversight, and Inequality

Claim: The collapse imposed the greatest cost on vulnerable people, while regulatory, market, and institutional power structures drifted by.

Rural and livestock-dependent communities suffered carcass overflow, water contamination, and disease risk—all while lacking disposal infrastructure. Health systems in rural areas had to absorb rises in disease burdens.

The pharmaceutical and veterinary markets propelled diclofenac’s spread: cheap generics flooded supply channels. The safer alternative drug meloxicam, though later proven non-toxic to vultures, remained costlier and slower to adopt.

Regulators acted too late. India officially banned veterinary diclofenac in 2006, but residues persisted in carcasses years later, and illegal usage continued.

Across national borders, the problem persisted in adjacent countries. Some veterinary NSAIDs (e.g., aceclofenac, ketoprofen) also posed risks. Enforcement remained patchy.

Thus, the weakest bore the shock; institutional failures magnified it.

Fragility Laid Bare: Ecological and Systemic Lessons

Claim: The vulture crisis is a stark lesson in nonlinearity, keystone roles, and systemic fragility.

Vultures are keystone species: roles few others can fill. Their near disappearance revealed how little redundancy some ecological niches have. Remove one actor, and the cascade spreads.

Many losses operate under thresholds. Once a tipping point is crossed—here, vulture numbers so low—recovery is slow, uncertain, and may never return to the prior equilibrium.

Legacy effects endure. Even years after the ban, vultures continue to die from diclofenac residues, population recovery is sluggish, and ecological gaps persist.

Moreover, the collapse-imposed costs on systems: human health, waste, economies, traditions—all had to absorb the burden. Nature’s services were treated as optional until they failed.

In this dramatic case, a small change—a veterinary drug—triggered a systemic rupture.

Rebuilding the Cleaners: Paths to Recovery

Claim: Recovery is possible, but only through holistic, justice-oriented, and sustained interventions.

Meloxicam has been demonstrated as safe for vultures and serves as a critical substitute for diclofenac. Widespread adoption must be universal, affordable, and enforced.

Strict bans and legal enforcement must be upheld; violations punished; oversight made real. Multi-dose human vials must be regulated to prevent diversion into veterinary use.

Captive breeding and reintroduction programs are essential. So are “vulture restaurants” or safe carcass feeding zones, where vetted carcasses free of residues can sustain wild populations.

Communities must be partners, especially pastoralists, farmers, and religious communities. Their incentives, traditions, and knowledge must shape solutions.

Health systems need to upgrade carcass disposal, surveillance, and sanitation in vulnerable zones.

And above all, we must monitor other NSAIDs and ecological threats vigilantly.

Recovery will be slow, full of risk, but refusing to do the work means further collapses.

Conclusion

The Vulture Catastrophe is not a relic of conservation history—it is a vivid warning. A single veterinary drug triggered the near collapse of India’s vultures. The fallout was human, ecological, cultural, and institutional.

We learned that ecological balance is fragile; that some species’ roles cannot be replaced; that justice, oversight, humility, and foresight matter.

Will we restore vultures—and with them, a measure of sanity in policy and ecology? Or will we keep treating life’s systems as modular, ignoring the cost of erasing their links?

Author’s Note

I chose this story because it compresses many ecological lessons into one tragic arc. It shows how small decisions—drug formulation, regulation, markets—can ripple into human death, cultural collapse, systemic failure. If students, citizens, policymakers take one thing from this—it is this: nature’s silent engineers matter deeply, and we ignore them at our peril.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References & Further Reading

- Diclofenac poisoning is widespread in declining vulture populations across the Indian subcontinent —PubMed

- Removing the Threat of Diclofenac to Critically Endangered Asian Vultures — study of meloxicam safety PMC

- The Social Costs of Keystone Species Collapse: Evidence from the Decline of Vultures in India — economic-ecological analysis Becker Friedman Institute

- When India’s vulture population collapsed, half a million human deaths followed — EPIC article summarizing health impacts EPIC

- Vulture decline in India linked to death of 500,000 people, study suggests — 4vultures blog Vulture Conservation Foundation

- How decline of Indian vultures led to 500,000 human deaths — EPIC summary EPIC

- Vulture conservation in India boosted by additional veterinary drug ban — update on regulatory actions BirdLife International

- Indian vulture crisis — overview of decline & causes Wikipedia

- Decline in Vulture population leading to health crisis in India, costing nearly 70 billion & 5 lakh deaths — news summary EPIC

- Veterinary drugs impact on South Asian vultures — background & policy commentary Cambridge University Press & Assessment