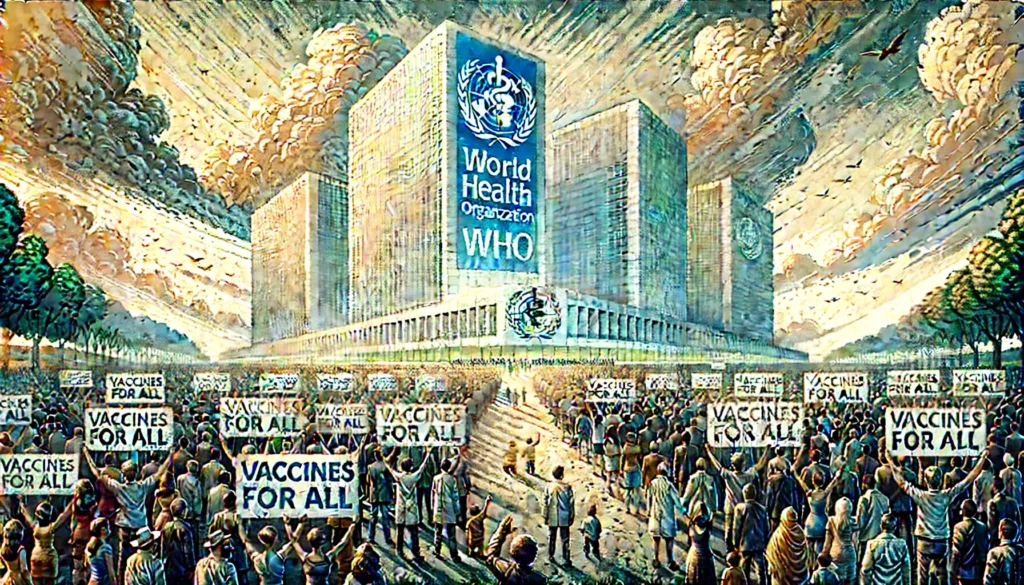

Fun Fact: This is the first time in history that nearly every nation, except one of the most powerful, has come together to sign a treaty to combat future pandemics — a moment as unique as it is urgent.

In a world still healing from the scars of COVID-19, something remarkable just happened. In a historic move at the World Health Organisation (WHO) headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, nations across the globe came together to sign the first global pandemic treaty, notably without the involvement of the United States.

Yes, you read that right.

While the US — home to the world’s most powerful pharmaceutical companies and medical research institutions — chose to sit this one out, the rest of the world moved forward. This treaty isn’t just a policy document; it’s a collective vow to do better the next time a pandemic strikes. And given the last one, that bar is pretty high.

Why a Pandemic Treaty?

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed some painful truths: rich nations got vaccines first, poor countries waited months or even years, and essential scientific data wasn’t always shared fairly. The imbalance was global and deadly.

During the crisis, vaccine inequity cost lives. While countries like the United Kingdom and Germany vaccinated their citizens multiple times over, nations in Africa and parts of Asia struggled to secure even their first doses.

That’s what this new Global Pandemic Treaty is trying to fix. Led by the World Health Organisation (WHO), the global authority on health matters, the treaty lays out a series of measures designed to:

- Share scientific data like virus samples and genome sequences more rapidly and fairly.

- Ensure equitable distribution of vaccines, drugs, and diagnostics in future pandemics.

- Promote technology transfer so that low-income countries can manufacture vaccines locally.

- Attach access conditions to publicly funded research, ensuring life-saving products are shared.

The Key Features of the Treaty

Sharing Pathogen Data for Global Good

At the core of the treaty is a system called Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing (PABS). It’s a trade-off: countries share critical data about viruses (like COVID-19 variants), and in return, pharmaceutical companies agree to share vaccines and medicines more equitably.

This idea is simple — if a lab in Nigeria detects a dangerous flu strain early, the world should know immediately, and that same lab should be among the first to receive the vaccine made from that data.

20% Commitment to WHO

Any pharmaceutical company (like Pfizer, Moderna, or Serum Institute of India — all of which develop and manufacture vaccines) participating in this treaty must commit to giving 20% of their pandemic-related products — vaccines, drugs, diagnostics — to the WHO. These supplies will then be distributed based on urgency and need, not wealth or power.

Conditions on Publicly Funded Research

Governments will now be asked to attach specific conditions when funding research into new vaccines and drugs. These include:

- Affordable pricing

- Licensing to other manufacturers

- Sharing clinical trial data publicly

This helps ensure that vaccines developed with public funds don’t end up as exclusive products affordable only to the rich.

No USA, No Problem?

Let’s address the elephant not in the room — the United States of America.

Despite its scientific leadership, the US withdrew from treaty talks on the very day President Donald Trump took office. His administration was often sceptical of global agreements, and this decision echoed that approach.

Why does this matter?

The US is home to some of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, like:

- Pfizer – An American multinational pharmaceutical giant known for creating one of the first widely used COVID-19 vaccines.

- Moderna – A biotech firm specialising in mrna technology used in vaccines.

- Johnson & Johnson – A health and consumer goods company that also developed a COVID-19 vaccine.

Without their formal participation, the treaty has less leverage over how these companies behave in the next crisis.

Still, the absence of the US also unified the rest of the world. In the words of Lawrence Gostin, a global health expert from Georgetown University, the treaty is a “reaction to Donald Trump” and a sign that “the world came together” in defiance of anti-globalism.

Voices from the Frontlines

The article quotes several key figures involved in making this treaty a reality:

- Precious Matsoso, co-chair of the treaty negotiating body, admitted: “I even have goosebumps because I can’t believe we finally finished.”

- Michelle Childs, from the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (a Geneva-based non-profit that promotes affordable medicine), emphasised how important it was to reassure poor countries that the inequities seen during COVID-19 won’t be repeated.

These voices reflect just how difficult — and emotional — this agreement has been.

Challenges Ahead

While the treaty’s intentions are noble, there are practical hurdles:

- Implementation: Countries need to turn this into national laws and procedures. That could take months or years.

- Compliance: Without enforcement, how can we be sure pharmaceutical companies will keep their promises?

- Incentives for Innovation: Industry leaders are worried this treaty may reduce profits and discourage investment in vaccine research.

A representative from the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) — an organisation that speaks for drug companies worldwide — stressed the importance of creating a “practical plan” that continues to incentivise innovation.

A Future of Shared Science

One of the most exciting outcomes of this treaty could be the normalisation of open science.

Guy Cochrane, who runs the European Nucleotide Archive (a major scientific data hub in the UK), stated it beautifully: “One of the greatest benefits that can be shared is the data and the scientific activity around the data.”

If we can make this work, we’re not just preparing for the next pandemic — we’re building a new model for how the world shares health knowledge.

What This Means for India and Other Developing Nations

For countries like India, Brazil, Nigeria, and many in South Asia and Africa, this treaty is more than just paperwork. It represents:

- Access to life-saving tools without delays

- Support for local manufacturing through tech transfers

- Representation in global health decisions

India, already a key vaccine manufacturer through firms like Serum Institute of India (the world’s largest vaccine producer), stands to play a leadership role in this new global framework.

Conclusion: A New Chapter in Global Health

We don’t know when the next pandemic will strike — but thanks to this treaty, the world may be better prepared. It’s not perfect. It doesn’t include everyone. But it’s a hopeful sign that lessons were learned from COVID-19.

It shows that global cooperation is not only possible — it’s necessary.

Let’s hold our leaders and institutions accountable to make sure this treaty doesn’t just sit in a drawer, but saves lives when it matters most.

Author’s Note

As someone deeply interested in global health equity, I found this story inspiring. It shows the power of persistence, cooperation, and the courage to act even when major players walk away. Let’s keep pushing for a world where no one is left behind in the fight against disease.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.