Fun fact: Indigenous peoples manage or influence lands that hold about 80% of Earth’s biodiversity, even though they represent only a small fraction of the world’s population.

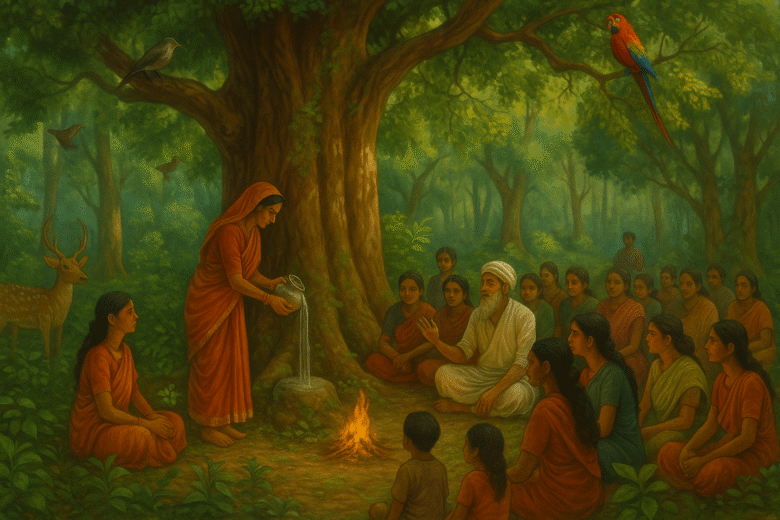

The New Environmental Stewards: Indigenous Knowledge in Conservation is about what those communities teach us about protecting nature—and why ignoring their voices is both foolish and costly. From sacred groves in India to Amazon tribes’ forest stewardship, indigenous knowledge is increasingly seen not just as a cultural treasure, but a crucial key to biodiversity and climate solutions.

Why Indigenous Lands Are Biodiversity Hotspots

Indigenous territories are often healthier ecosystems. Their forests tend to store more carbon, species richness is often higher, and deforestation rates are generally lower than in comparable non-indigenous lands. This is not by accident or romantic myth—it’s because many indigenous systems are built on deep local knowledge, spiritual and cultural values, long-term thinking, and a sense of kinship with nature.

In the Amazon, for example, indigenous lands act as effective carbon sinks and resist deforestation better than many State-protected forests. Lands legally held by Indigenous Peoples are observed to struggle less with encroachment and illegal logging. This shows that if you want ecosystems that function well, giving local and indigenous communities strong legal rights and a role in governance makes a difference. Scientific evidence confirms that when Indigenous communities have land tenure (the legal right to the land), ecological outcomes improve.

Traditional Knowledge in Practice: Sacred Groves and Agroforestry

Sacred groves in India are one of the most compelling examples. In states like Karnataka, Kerala, Uttarakhand and Manipur, groves of forest are preserved not by government but by communities, guided by custom and belief. These groves harbour endemic species, sometimes rarer and more threatened than those in official protected areas. They also preserve soil quality, water sources, and cultural continuity.

In Uttarakhand, a recent exercise mapped over 160 sacred natural sites—including groves, forests, alpine meadows, and high-altitude lakes. These areas are rich in rare and endangered plants and serve as refuges for species under climate stress. The traditions of reverence, ritual, and community protection often mean these places are healthier and better preserved than many publicly protected reserves.

Elsewhere, in the Amazon, Indigenous agroforestry practices blend cultivation with forest conservation. Communities nurture forest plots by selecting useful species, maintaining tree cover, and regenerating secondary forests during fallow periods. Such systems support biodiversity, soil health, and carbon storage—and are resilient to changes like climate fluctuations or market pressures.

Rights, Recognition, and Governance

One reason indigenous knowledge is making a comeback is that people are realizing that culture and rights matter, not just ecology. Where communities have formal legal rights—titles, autonomous governance, recognized sacred sites—they tend to do better in conservation.

A vivid case: the Dongria Kondh people in Odisha, India, who resisted mining in the sacred Niyamgiri hills. Their opposition succeeded when courts recognized that their relationship with the land is not just spiritual but ecological and essential. Their authority over the land helped protect massive tracts of pristine forest.

In Amazonia, organizations are pushing for policies that grant Indigenous Peoples more voice in land use, regulation, and environmental protection. Some governments are adopting participatory mapping (letting indigenous people map their own forests), using community monitoring (with local people as forest guards), and reinforcing customary laws alongside State laws.

Challenges—and Why This Work Is Not Enough

Indigenous stewardship is powerful, but far from a magic bullet. Some sacred groves are shrinking, under pressure from urbanization, tourism, climate change, and loss of traditional beliefs among youth.

Governance can be undermined by weak legal recognition, overlapping claims, corruption, or economic pressures (for example, extractive industries pushing for access). Also, knowledge transmission is sometimes fragile—oral traditions, rituals, plant knowledge can erode when younger generations migrate to cities or when external culture overwhelms local culture.

Agroforestry or sacred site protection may offer strong local benefits, but often lack funding, scientific support, or institutional backing. Some conservation frameworks still treat indigenous knowledge as decorative rather than central.

Lessons We Could All Use

What can governments, conservationists, businesses, and ordinary people learn from indigenous stewards?

Respect and integrate Indigenous Rights: Land rights, legal titles, and free, prior, and informed consent are more than paperwork—they are central to conservation success.

Combine Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge: Many best practices arise when the two are used together. For example, selecting indicator species, managing fire risk, restoring soils, and mapping ecosystems.

Support Cultural Transmission: Schools, apprenticeships, local language, and ritual help keep knowledge alive.

Build Policy and Financial Support: Conservation funding often bypasses local communities. Indigenous stewards need funding, recognition, infrastructure, and legal protection, not lip service.

Reframe Conservation Definitions: Conservation isn’t only about setting aside parks; it’s about sustaining livelihoods, allowing sustainable use, and respecting cultural values.

Conclusion

The New Environmental Stewards: Indigenous Knowledge in Conservation isn’t just a hopeful slogan—it’s a necessary shift. If we continue thinking of conservation only in terms of State control or technology, we lose what makes ecosystems resilient in the first place. Indigenous communities have been guardians of biodiversity for centuries, often protecting far more than governments realize. We could learn from them—not only because it’s just, but because if we don’t, we all pay the price.

Author’s Note

I wrote this because too many conservation narratives treat indigenous voices like optional extras. On the contrary, they are central—they are stewards, knowledge-keepers, partners. If they are sidelined, we lose not only nature but our humanity.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- Sacred Groves, the secret wizards of conservation – IUCN Blog

- Conservation and Management of Sacred Groves, Myths and Practices – LS Kandari et al.

- Alternative Ways of Ecological Conservation: A Study of Sacred Groves – Mallick et al.

- Indigenous-led Conservation in the Amazon: a chronicle at Amazon Frontlines

- The Ancestral Forest: How Indigenous Peoples Transformed the Amazon into a Vast Garden – Rainforest Foundation

- Scientific Evidence Points to Indigenous Peoples’ Forest Management as Key to Climate Change Mitigation

- Sacred Forest Biodiversity Conservation: Meta-analysis – Conservation Biology

Comments

Fantastic website. A lot of useful info here. I’m sending it to some buddies ans also sharing in delicious. And obviously, thanks in your effort!