Fun Fact: The Homeric epics like the Iliad and Odyssey were passed down orally for centuries before they were ever written down—yet the stories survived almost word-for-word.

Now think about how hard it is for you to remember a phone number without saving it. That contrast right there? That’s the cognitive distance between oral cultures and written ones. We live in a world dominated by text—tweets, notes, textbooks, legal documents, messages. But for thousands of years, humans relied on memory, voice, and rhythm to pass down everything from lineage to law. And here’s the kicker: our brains still carry the echoes of both traditions.

Let’s explore how memory works in oral vs. written cultures—and why it matters more today than we think.

The Oral Mind: Memory as a Muscle

Before printing presses and paperbacks, memory wasn’t just useful—it was survival.

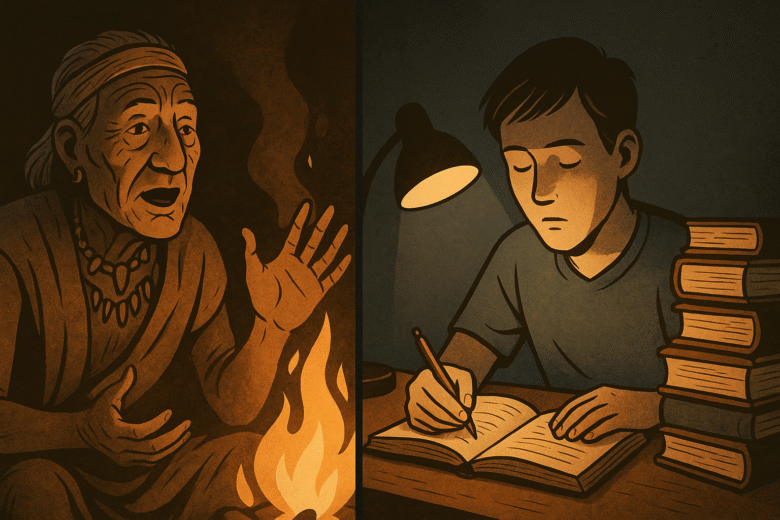

In oral cultures, everything—religion, history, medicine, farming, social rules—was passed down through speech. There was no text to check, no bookmarks to flip back to. Instead, memory was deeply embodied, rhythmic, and communal.

Mnemonics Were Life Tools

In the absence of writing, oral cultures developed stunning memory tools. Stories were told with formulaic phrases (“rosy-fingered dawn,” “swift-footed Achilles”), which acted like memory anchors. Repetition was deliberate. Song, rhyme, and rhythm weren’t stylistic choices—they were functional. They helped people remember 10,000-line epics without missing a beat.

Indian traditions, too, illustrate this. The Vedas were transmitted orally for over 1,000 years before being written down. The reciters followed strict phonetic precision, sometimes even visualizing sound patterns. That’s not memorization. That’s architecture.

Knowledge Was in the Performance

In oral cultures, knowledge wasn’t “owned” by individuals; it lived in the act of recitation. A skilled storyteller wasn’t just a narrator—he or she was a living archive. Memory was performative, contextual, and social. Forgetfulness wasn’t just a personal lapse; it could mean the loss of collective history.

The Written Word: External Memory

Now step into a world of paper and pens.

Writing, when it emerged, changed everything. It didn’t just preserve ideas—it restructured how we thought.

Writing as a “Second Brain”

With written language came the ability to store knowledge outside the human mind. You no longer needed to remember entire genealogies—you could refer to a scroll or a file. This allowed thought to become more abstract, analytical, and recursive. Writing slowed thought down, enabling reflection and re-reading.

Psychologist Walter Ong called writing a “technology that restructures thought.” It allowed for complexity but also reduced the cognitive demand for retention. Essentially, it was the birth of what cognitive scientists now call cognitive offloading—letting external tools carry the burden of memory.

But It Also Changed the Nature of Memory

In written cultures, we began to privilege data over delivery. Accuracy became more important than emotion. The “how” of memory (tone, voice, pause, gesture) became secondary to the “what” (the literal content). This led to more precise, verifiable records—but also to more isolated learning.

Instead of learning through oral apprenticeship, we started learning through private study. The memory became more internal, less social. Ironically, while writing preserved memory, it weakened our personal capacity to hold it.

Case Study: A Song vs. A Textbook

Let’s say you hear a folk song passed down for generations in a rural Indian village. It’s catchy, repetitive, emotional. Chances are you’ll remember it without even trying.

Now think of your school textbook. Even if it’s been read five times, its facts may fade the moment the exam is over.

This isn’t just about interest. It’s about memory design.

Oral culture embeds memory into experience—you sing it, dance it, live it. Written culture abstracts it—converting lived knowledge into symbols that require decoding.

This is why oral memory is embodied and participatory, while written memory is analytical and solitary.

The Brain Remembers Differently

Neuroscientific research backs this up.

Studies show that memory reinforced through music, rhythm, or narrative engages more areas of the brain—particularly the hippocampus and motor cortex. In contrast, reading silently activates the visual and language-processing centers, but less so the emotional or motor circuits.

Oral memory is multisensory. Written memory is linear. One uses the whole body. The other, mainly the eyes and mind.

That’s why people from oral traditions often have stronger working memories. It’s not because they’re smarter—it’s because their brains are trained to remember differently.

When the Two Worlds Collide

Today, we live in hybrid worlds.

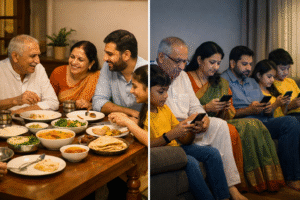

An Indian grandmother tells a bedtime story orally, while her grandson types his science notes into Google Docs. One relies on embodied performance, the other on digital storage. Neither is “better”—but they are fundamentally different.

And here’s the interesting part: we might be losing the oral skillset altogether.

As we become more dependent on devices, our need to remember shrinks. We’ve outsourced birthdays to calendars, spelling to autocorrect, directions to GPS (Global Positioning System). We no longer train memory; we delegate it.

But memory isn’t just about information. It’s about identity. When a culture forgets how to remember, it forgets itself.

Can We Learn From Oral Cultures?

Absolutely. Here’s what oral cultures can teach our digital minds:

Repetition is a strength, not a flaw.

In oral storytelling, repetition is a memory technique. Maybe that’s why you still remember nursery rhymes, but not last week’s PowerPoint.

Emotion aids retention.

Oral narratives engage empathy. You remember a story you felt—not just read.

Memory is communal.

In oral traditions, memory is shared through performance. Maybe classrooms need more conversations, fewer PDFs.

Active recall beats passive reading.

Oral learners constantly retrieve information through speech. Writing something once may not be enough—but retelling it? That sticks.

Conclusion: Don’t Just Read—Remember

We live in an age where forgetting is easy—because remembering is optional.

But maybe it’s time to relearn the art of memory—not just through apps and reminders, but through rhythm, repetition, and retelling. Our ancestors remembered lineages, laws, and lore without a single scrap of paper. Not because they had better brains, but because they used memory as a living, breathing tool.

So the next time you want to learn something, don’t just write it down. Say it out loud. Sing it. Share it. Make it stick.

Because when memory is active, culture stays alive.

Author’s Note

I wrote this while trying to recall a poem my grandmother used to recite. I couldn’t. But I remembered the tone of her voice, the way she paused, the way she smiled mid-line. That, too, is memory. May we not lose it.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

-

- Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/orality-and-literacy-9780415281296 - Rubin, David C. Memory in Oral Traditions

https://www.amazon.in/Memory-Oral-Traditions-David-Rubin/dp/0195169129 - The Cognitive Science of Oral Culture:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7356075/ - How Writing Reshaped Human Thought (BBC Future):

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20191113-how-writing-changed-thinking - https://gedis.medium.com/mindfulness-and-the-brain-from-caveman-chaos-to-popcorn-ponderings-e3e77a0a8a09

- https://www.thetribune.ca/is-oral-tradition-dead

- Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word