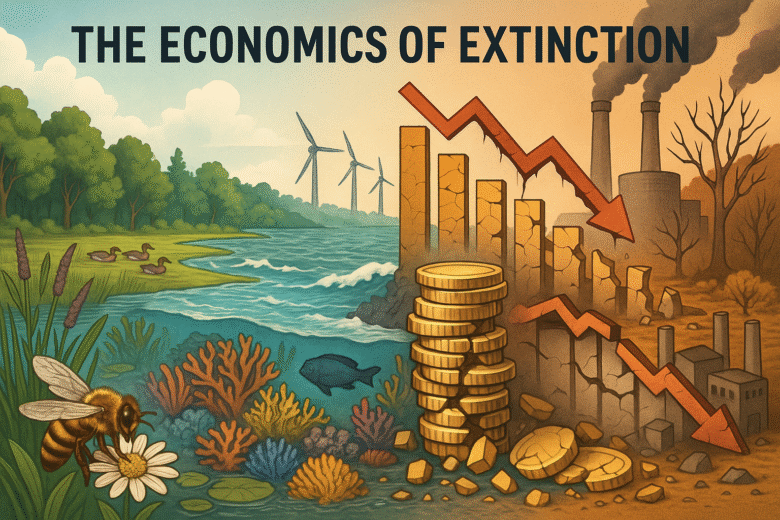

Fun fact: nature delivers services worth an estimated US$150 trillion a year—roughly double the world’s GDP. That’s the scale of what we stand to lose when ecosystems collapse.

Welcome to The Economics of Extinction, where we explore what happens to human lives, businesses, and whole economies when the buzz of bees, the protection of wetlands, or the balance of coral reefs fade away. Because as those go, so do billions—sometimes trillions—in value, security, and common sense.

Nature’s True Value: More Than a Charity Case

We often think of nature as “nice to have,” but it’s much more: it’s indispensable capital. Wild pollinators produce food; wetlands buffer storms; forests store carbon and clean water. Recent analyses show that many sectors—agriculture, fisheries, food and beverages—depend heavily on ecosystem services. In fact, over half of global GDP is “moderately or highly” dependent on nature’s services. Those numbers translate into real risks. When ecosystems falter—due to climate change, pollution, habitat loss—the resulting costs aren’t just environmental losses, they are economic losses too.

Losses We’re Already Paying For

The damage is not waiting for some far future. We’re already seeing economic losses of more than US$5 trillion per year from declining ecosystem services. Think fewer fish, less fertile soil, weaker flood defences, poorer air and water quality. Some reports warn that by 2030, the collapse of select ecosystem services—marine fisheries, pollination, forests—could shave US$2.7 trillion annually off global GDP. Countries in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa might suffer the worst percentage hits, since their economies are strongly tied to nature for food, livelihoods, and protection against extreme events.

Natural Capital Accounting: Putting a Price Tag on Nature

To stop the bleeding, more governments and businesses are trying to value what was once “free.” Natural Capital Accounting (NCA) is one such tool. It means measuring, quantifying, sometimes putting a monetary value on the services nature provides—so that decisions can weigh trade-offs properly.

- A case in India: Ambuja Cement (part of Holcim) has piloted ecosystem accounting at quarry sites, measuring water use, biodiversity, and restoration under different scenarios, to compare costs and benefits of restoration.

- Another example: a Namibian tannery, Nakara Leather Pty Ltd, used NCA to align its business practices with environmental responsibility, tracking the use of water, energy, land, biodiversity, and waste in its operations.

These examples show that going beyond abstract moral claims to concrete numbers helps businesses see where losses, inefficiencies or risks lie—and in many cases, saves money or reduces risk in the long run.

The Costs of Doing (Too Little) or Doing It Late

Delaying protective actions or undervaluing natural capital tends to multiply costs. Some critical tipping points are at hand—for example, the collapse of pollinator populations, or the loss of coastal mangroves that protect against storms. Once passed, those damages are very hard or impossible to reverse. The economic damages rise steeply with delay.

Also, many economic models historically ignored nature loss or treated it as an externality. But recent reports show that if ecosystem declines continue unchecked, by 2030 global output could drop by more than 2-3 percent of GDP. This isn’t just numbers: lives will be affected—rural communities, farmers, coastal dwellers, people already vulnerable to climate and health risks.

Business, Policy, and Innovation: Where We Can Turn the Tide

Some positive shifts are already underway:

- More companies and investors are integrating natural capital into their risk assessments. They’re asking: “What does this project cost if we lose soil fertility or water quality?” or “How much would flooding cost us if we lose mangroves?”

- Governments are exploring “nature-smart” policies: reforming subsidies that encourage environmental harm; investing in restoration; protecting key ecosystems. These policies can be win-wins: better nature, better long-term economic health.

- Innovative business models are emerging: payments for ecosystem services (e.g., paying farmers or communities to conserve rather than degrade forests), “true cost accounting” that internalizes what used to be external.

The Moral Case Is Real—and Economically Material

It’s tempting to treat biodiversity loss as a moral issue only—something for environmentalists. But when we translate biodiversity into dollars and risks, it becomes material to everyone: governments, businesses, and citizens. Ignoring these costs is essentially borrowing from future generations without telling them.

Conclusion

The Economics of Extinction isn’t just a provocative phrase—it’s a warning. Nature’s daily services, once taken for granted, are already slipping, and with them go economic stability, food security, climate resilience, and the livelihoods of billions. We need to stop imagining that nature’s wealth is endless, or that its loss is someone else’s problem.

Author’s Note

I wrote this because too often biodiversity loss is whispered about, not demanded. Dollars and cents matter to most of us—and when the loss of bees, forests, reefs, and wetlands starts to cost us personally, we notice. Let’s pay attention now, not later.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- The BCG Report: Biodiversity loss in business value and ecosystem dependency

- World Bank: The Economic Case for Nature & losses of ecosystem services

- UNU-FLORES Case Study: Nakara Leather NCA implementation

- [SEEA / Holcim & Ambuja Cement Case Studies] (Natural Capital Accounting & Valuation of Ecosystem Services project)

Comments

Hi! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after checking through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely delighted I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back often!