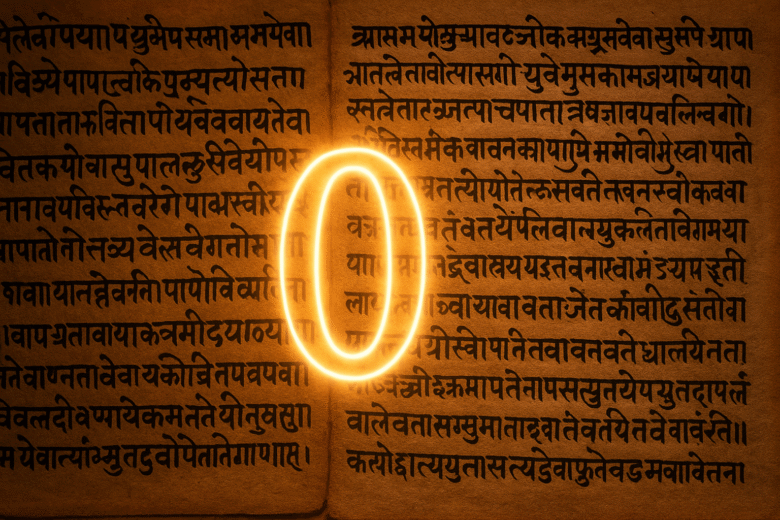

Fun fact: The symbol for zero (“0”) and the concept of using it as a number were first clearly recorded in India—over 1,500 years ago.

Zero is everywhere and nowhere. It’s on your calculator, your bank balance, your phone number, and your school exam results. Without zero, we wouldn’t have binary code. Without binary code, no computers. And without computers, well, you wouldn’t be reading this blog.

But for something so essential to modern life, zero had a shockingly rocky beginning. It took centuries for the world to accept it. And it all started in ancient India.

This is the story of the most powerful nothing in the world—zero—and how India gave it to the globe.

Why Zero Wasn’t Always Obvious

It’s easy to take zero for granted. After all, what’s simpler than “nothing”?

But the concept of zero as a number—not just a placeholder or a symbol of absence—was revolutionary. Many ancient civilizations had math systems, but few had a clear way to represent “nothing” within that system.

- Egyptians had no symbol for zero.

- Romans could build empires, but try doing long division with Roman numerals—you’ll quickly understand why they avoided math.

- Babylonians used a space or a dot to signify absence, but never developed zero as a full number.

Why the hesitation? Because nothingness was philosophical quicksand. How can “nothing” be something? To assign value to an absence required a complete shift in how we think.

India’s Mathematical Enlightenment

India, sometime between the 5th and 7th centuries CE (Common Era), became the birthplace of the numeral zero.

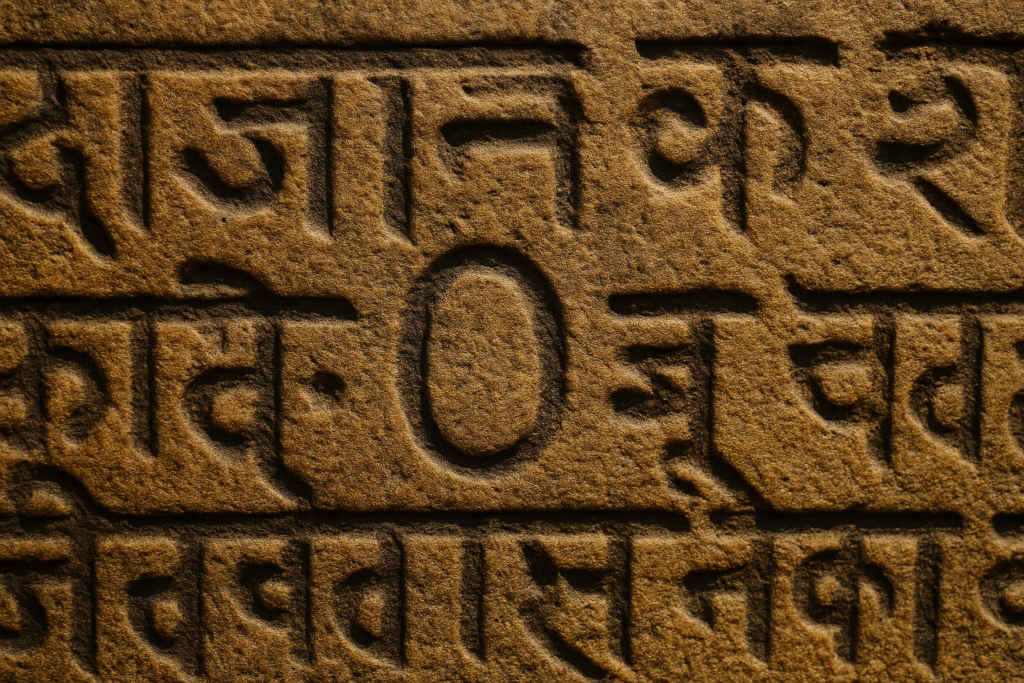

The first recorded use of a symbol for zero as part of a positional number system appears in a 9th-century inscription found in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh. But earlier, in the 5th century, the great Indian mathematician Aryabhata had already used a placeholder for zero in his astronomical calculations.

Then came Brahmagupta (598–668 CE), another Indian genius. In his seminal text Brahmasphutasiddhanta, he didn’t just use zero—he defined it. He gave rules for arithmetic involving zero:

- Zero plus a number is the number.

- Zero times any number is zero.

- A number minus itself is zero.

That might sound basic now—but back then, it was profound.

More importantly, he treated zero as a number in its own right. Not just a blank space, but a player on the field.

Zero Goes Global (Very Slowly)

The decimal system (base 10), along with the digit “0”, made its way from India to the Islamic world via trade routes and scholarly exchange.

In Baghdad, Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi wrote about the Indian number system in the 9th century. This led to the Arabic numeral system—which included zero—spreading across the Islamic empire.

Eventually, these “Arabic numerals” reached Europe through translations of Arabic texts into Latin in places like Spain during the 12th century.

Europe resisted at first. Church authorities were suspicious. Merchants found zero confusing. Roman numerals were clunky but familiar.

But by the 15th century, merchants, bankers, and mathematicians embraced the simplicity of the new system—and zero was in.

So the credit chain is long: India → Islamic world → Europe → the rest of us.

Case Study: Without Zero, No Computers

Every modern computer runs on binary code—a language of 1s and 0s.

The “0” in binary isn’t just a stand-in for “off” or “false.” It’s the foundation of data, logic, and storage. Without zero, binary collapses. And with it, everything digital: your phone, your internet, your WhatsApp chats, your bank account.

Zero is the gatekeeper of the digital age. And its passport was stamped in India.

The Philosophy of Nothingness

India didn’t just invent zero—it embraced nothingness as a philosophical idea.

In Hindu and Buddhist philosophies, the idea of “shunyata” (meaning emptiness or void) existed long before the development of the mathematical zero. This spiritual acceptance of nothingness made it easier for Indian scholars to see “zero” not as a threat to logic, but as a vital part of it.

Where Western thinkers struggled with the paradox of “something that is nothing,” Indian thinkers had already built philosophical frameworks that made room for the void.

Mathematics didn’t create zero. A worldview did.

What We Owe to India’s Invisible Export

Let’s be clear: zero is not just a symbol. It is an idea, a tool, and a revolution.

India didn’t just invent zero—it gifted the world an intellectual breakthrough that changed how we calculate, trade, build, and think. It’s not an exaggeration to say that without India’s contribution, modern science and technology would have been crippled at birth.

The irony? For a number that represents “nothing,” zero changed everything.

Why It Still Matters

In an era obsessed with innovation, we often forget where innovation begins—not in shiny new gadgets, but in ideas.

Zero is proof that intellectual courage matters. It took centuries for people to accept the value of “nothing.” Now we build satellites and simulate universes with it.

In a world drowning in noise, zero is the silent genius. And it came from India.

Conclusion: Celebrate the Nothing That Changed Everything

The next time you swipe your card, calculate your taxes, or even type a password—pause.

Think about that tiny, round digit. The one no one wanted at first. The one born in the ancient subcontinent, carried by scholars and traders, resisted by empires, and eventually embraced by the entire planet.

The history of zero is not a footnote. It’s a headline.

And it might just be India’s most invisible—and most important—export.

Author’s Note

Writing about zero made me realize just how profound “nothing” can be. In a world that celebrates “something,” maybe it’s time we gave zero its due. After all, every great equation begins with it.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.