Fun fact: one of the world’s oldest known monuments, Göbekli Tepe in present-day Turkey, was built around 11,000 years ago — long before agriculture, cities, or writing.

We’ve been building monuments almost from the moment we gathered in groups. Why? Because building is more than creating. In asking Why Do We Build Monuments? we dig into what it means to remember, to assert, and to last.

Monuments speak for societies. They fix narratives, enshrine values, and carve legacies in stone (or metal, or glass). They are silent witnesses — and loud statements. In this article, I’ll argue: we build monuments because we’re scared to be forgotten, because power loves permanence, and because memory always needs a stage to perform on.

Memory and the Urge to Remember

At its heart, building a monument is an act of memory. We erect statues, mausoleums, and memorial walls to anchor the past in the present. Without such anchors, the flood of time would erase stories.

Consider war memorials. They don’t just list names — they force you to pause, to see lives behind dates. In places where oral histories fade, monuments become schoolbooks in stone for future generations. They answer questions like: “Who mattered? What do we honour?” Monuments codify those answers into public space.

Yet memory is selective. What and whom a society chooses to memorialize — and omit — reveals much about its power dynamics. Monuments don’t just preserve memory; they shape it.

Power, Authority, and Symbolic Domination

A monument is also a power play. Emperors, kings, modern states — all have tried to inscribe their rule into the landscape. The message is: “I was here. My reign matters. My version of history matters.”

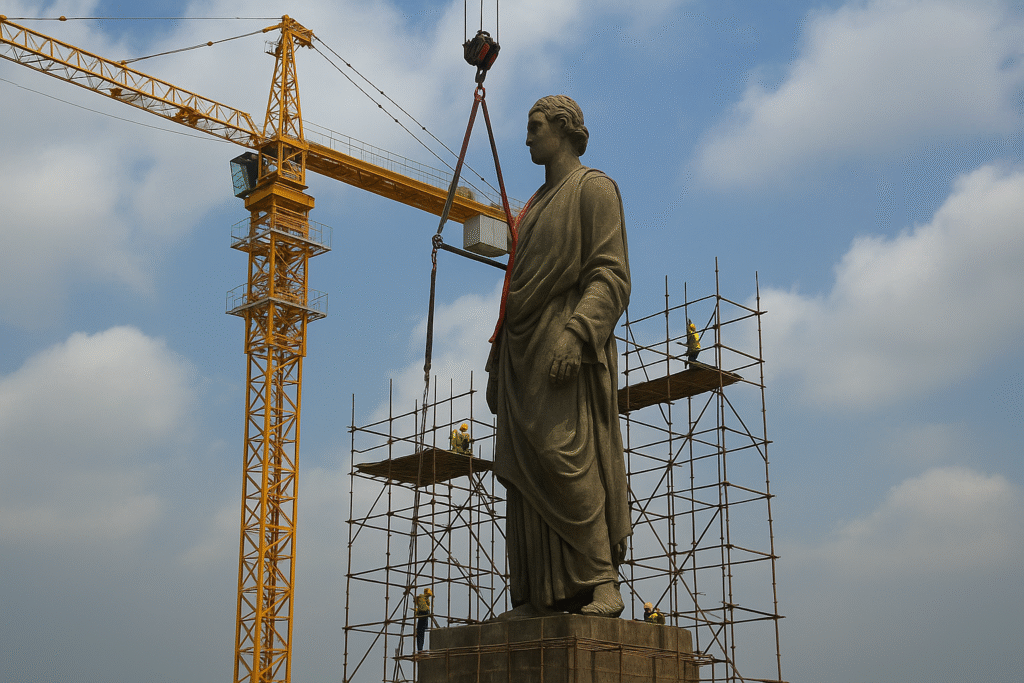

From the pyramids of Egypt to the triumphal arches of Rome, rulers have used scale, artistry, and placement to cement authority. A towering statue in a city square is a non-verbal announcement: “Look at me. Remember me. Believe in me.”

In modern times, this plays out too. Governments commission monuments to heroes, martyrs, and revolutions — choosing which heroes, which martyrs, which version of the revolution. Sometimes dissenters topple or reclaim them. Monuments are contested terrains of meaning.

When statues are torn down — whether in revolutions or moments of reckoning — it’s not just vandalism. It’s symbolic re-writing: “We no longer endorse your version of history.”

Permanence, Legacy, and the Illusion of Immortality

We build monuments because we crave permanence — something outlasts us, something that declares: “I was here.” Stone, bronze, and concrete feel immortal. But of course, they aren’t. Weather, neglect, war, and ideology all chip away.

Still, the illusion matters. A monument’s ambition is temporal transcendence. If a society can’t survive forever, its monuments can try. They are bets against oblivion.

Yet therein lies irony: often the very instability monuments hope to defy becomes their undoing. Empires fall, ideologies shift, and stones are defaced. Even when monuments survive, their meanings shift as generations reinterpret them.

Case Studies: Monumental Memory in Practice

Göbekli Tepe – Built in the 10th millennium BCE, it’s not a tomb or temple in the traditional sense but a megalithic ritual site. Its existence suggests that even early hunter-gatherers felt a need for sacred memory in stone.

Mutiny Memorial, Delhi (now Ajitgarh) – This colonial-era monument in New Delhi was erected by the British to commemorate their view of the 1857 rebellion. After India’s independence, the name and interpretation changed, showing how monuments can be recontextualized.

Siegestor, Munich – Initially a triumphal arch celebrating military victory, it now carries a new inscription. It now stands “dedicated to victory, destroyed by war, urging peace.” It embodies how monuments can be repurposed.

Solovetsky Stone (Saint Petersburg) – A simple granite boulder placed to commemorate victims of political repression in the Soviet era. In its quiet presence and shifting usage during memorial events, it shows how monumentality can be subtle, not grandiose.

Rhodes Memorial, Cape Town – Once a tribute to colonial figure Cecil Rhodes, it’s now part of ongoing debates about who we choose to celebrate and why.

These examples underline that monuments are not fixed. They live, breathe, and sometimes fight back.

The Paradox of Permanence

Monuments promise permanence, but they are inherently mortal. They age, crack, fade. Their symbolism ages faster. What was heroic in one era becomes problematic in another. A hero becomes a villain, and the monument becomes contested.

Memory is dynamic. The meaning a statue held in 1900 may be alien today. The very permanence of monuments’ claim is what makes them vulnerable — because future societies may rewrite or remove what feels outdated or unjust.

Modern Monuments and the Digital Turn

Today’s “monuments” don’t have to be stone and bronze. Digital memorials, virtual monuments, and augmented reality markers are emerging. Think of online memorial pages, virtual reality reconstructions, or projection art on buildings.

These new forms both democratize and complicate memory. More people can participate, but also more narratives compete. Without gatekeepers of stone, memorialization becomes more plural — but also more chaotic.

Conclusion

We build monuments because we fear forgetting. Because power craves permanence. Because memory without a stage is ephemeral.

But the paradox is clear: monuments are both symbols of eternity and signs of vulnerability. They anchor memory, but require continual care. They assert authority, but invite resistance. They promise permanence, yet are subject to decay and reinterpretation.

If you walk through any city with open eyes, you’ll see them — monuments to kings, martyrs, ideas, eras. Each one asks: “Who am I to you? Who do you choose to remember? And who do you leave behind?”

Maybe monuments are less about what we fix in stone, and more about who we are in the moment that they are erected. In valuing a monument, we value a story. In rejecting one, we attempt to reshape memory.

So next time you pass a statue or a memorial wall, don’t just glance. Listen. Ask: Why is this here? Whose memory lives? Whose is erased? In doing that, you become part of the dialogue that monuments were built to start.

Author’s Note

Monuments shape not just our landscapes, but our minds. In exploring their power, we probe how societies remember — and what they choose to forget. I’d love to hear your stories of monuments (personal, local, or national) that moved you or made you question whose memory they carry.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- An Overview of the Scholarly Literature on Commemoration (National Park Service)

- Monuments and Memory: Power, Politics, and the Debate Over What We Choose to Remember

- Monuments and Collective Memory (Medium / Philosophy & Society)

- Monuments, Memorials, and Intangible Heritage (Radical History Review)

- The Power and Promise of Public Memory (Haas Institute / Belonging at Berkeley)

- The Role of Memorials in Preserving History (United Nations)

- The History of Monument-Making and Its Cultural Significance

- Public Monuments and Public Memory (The Public Discourse)

Comments

Your blog is a beacon of light in the often murky waters of online content. Your thoughtful analysis and insightful commentary never fail to leave a lasting impression. Keep up the amazing work!

Thank you for your contribution.