Fun Fact: The number zero (0), which seems so ordinary today, was once banned, feared, and even associated with the devil in medieval Europe.

Imagine trying to explain your age, count your salary, or measure a cup of rice—without using numbers. Hard to picture, right? Yet, for most of human history, counting was a deeply cultural act, shaped by necessity, geography, and even religion. In this blog titled “How We Count: A Global History of Numbers and Numerals,” we explore how different civilizations invented, shaped, and even argued over the symbols and systems we now take for granted.

Because counting is not just about math. It’s about power. It’s about belief. And it’s about how humans decided to make sense of the world—with fingers, bones, and sometimes, with gods.

Counting Before Numbers: Knots, Fingers, and Bones

Long before the first “1” was ever scratched onto stone, humans were counting—just not with numerals.

Tally marks on bones found in Africa (like the 44,000-year-old Lebombo bone) were among the first tools of prehistoric accountants.

In Peru, the Inca civilization used quipus—knotted strings—to keep records. Different knots, positions, and colours represented numbers and categories.

In many early societies, fingers and body parts were counting tools. The base-20 system used by the ancient Mayans is believed to come from counting both fingers and toes.

Counting wasn’t universal; it was local, functional, and full of personality.

Egyptian Tallies and Babylonian Brilliance

Egyptians: Counting for the Pharaohs

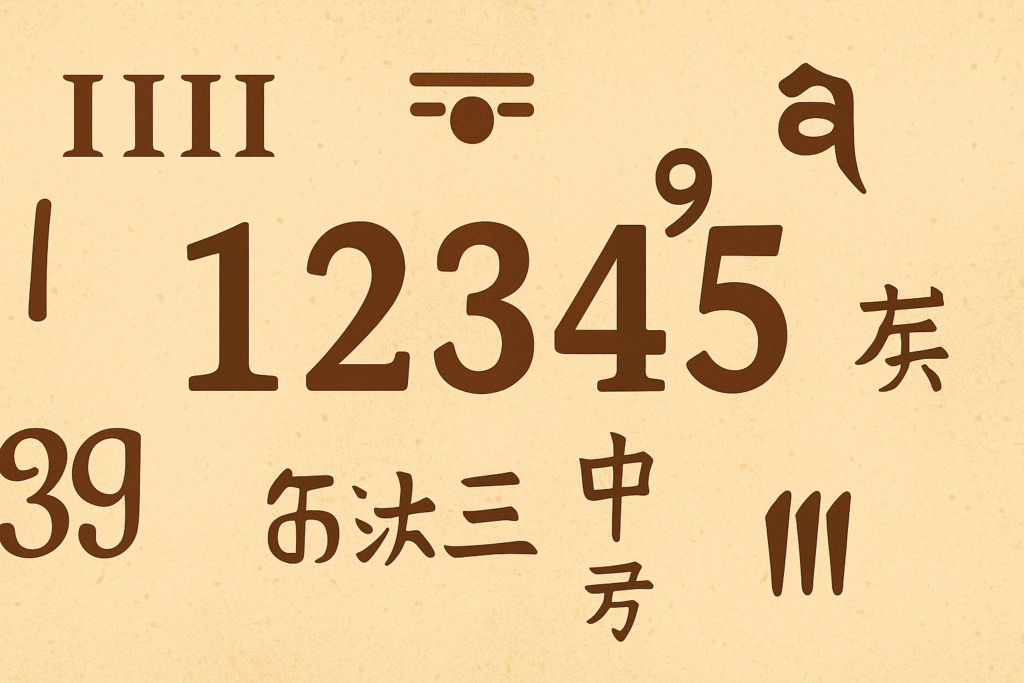

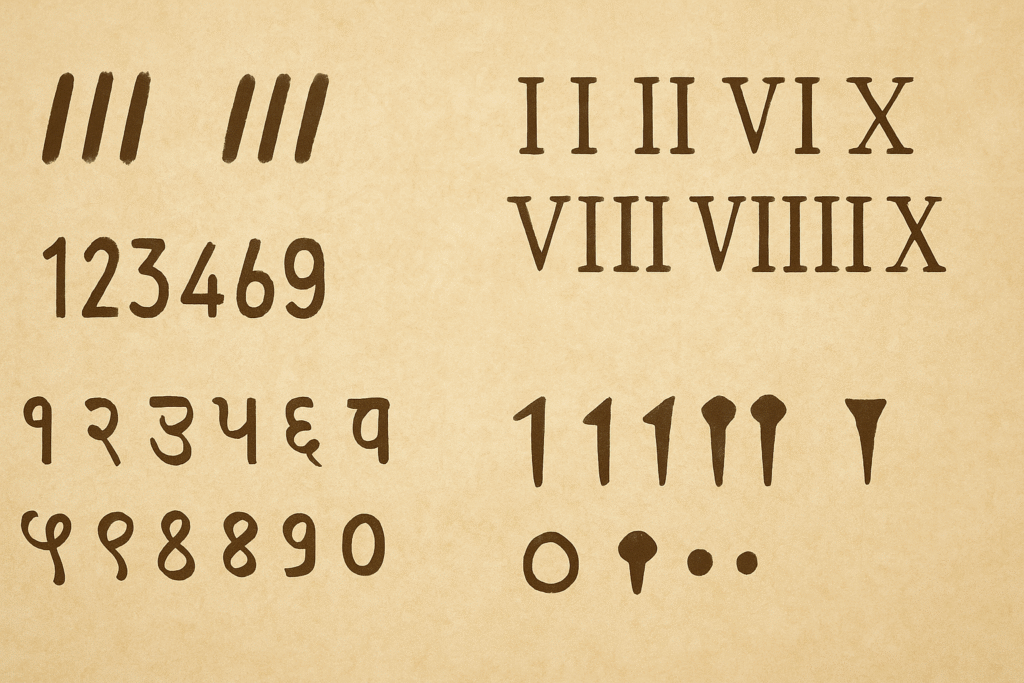

The ancient Egyptians created a base-10 system using simple pictures—like lines for 1s, heel bones for 10s, and spirals for 100s. Their numerals were written in hieroglyphics, and although they were efficient for counting grain or building pyramids, they lacked place value—so 100 always had to be written with the same symbol, over and over.

Babylonians: Math with a Twist

Far more advanced in calculation were the Babylonians, who invented a base-60 system (that’s why we have 60 minutes in an hour). They used wedge-shaped marks on clay tablets—cuneiform script—to represent their numbers.

But here’s the kicker: they had no real concept of zero—only a placeholder. That absence would haunt math for centuries.

The Indian Revolution: Zero, Place Value, and Decimal Brilliance

India gave the world two things it now couldn’t live without: zero (0) and the decimal system (base-10 with place value).

The Brahmi numerals, used around 300 BCE, eventually evolved into what we now call Hindu-Arabic numerals—the digits 0–9 that power modern computing.

Aryabhata (476–550 CE), an Indian mathematician, wrote about place value without zero.

Brahmagupta (598–668 CE) later formalized the rules of zero—not just as a placeholder but as a number in its own right. He even wrote equations like “zero divided by any number is zero.”

This wasn’t just math. It was a philosophical breakthrough—imagine naming “nothing.”

From India to the World: The Arabic Bridge

Although the digits were invented in India, it was the Islamic Golden Age scholars who spread them.

Mathematicians like Al-Khwarizmi (yes, that’s where the word algorithm comes from) translated Indian works into Arabic.

Al-Kindi, another Arab scholar, championed the system’s efficiency for commerce and astronomy.

By the 9th century, the numbers reached Baghdad, and from there, through North Africa and Spain, they entered Europe.

In this way, “Arabic numerals” became a misnomer—they were the Indian numerals, Arabic-transmitted.

Europe’s Reluctance—and the Zero Scare

You’d think Europeans would have adopted the system instantly. They didn’t.

Why?

They were hooked on Roman numerals, which were terrible for math. Try dividing CXLIV by XII without converting to modern digits.

Zero, especially, scared people. In Christian Europe, the idea of “nothingness” was associated with the void, the devil, and nihilism.

In 1299, Florence even banned the use of Arabic numerals, claiming they were easier to forge than Roman ones.

It took the influence of thinkers like Leonardo of Pisa—better known as Fibonacci—who wrote Liber Abaci in 1202, to begin to change minds. He showed how Indian-Arabic numerals made trade and taxes simpler.

Chinese Counting Rods and the Power of the Abacus

In China, numbers evolved differently.

The Chinese used counting rods laid out on a counting board in base-10.

They didn’t use positional zero until much later, but they excelled at visual computation using rods and later the abacus (or suanpan).

The abacus was more than just a calculator—it was a powerful tool for sharpening the brain. Even today, children trained on abacuses show faster mental arithmetic.

The Chinese numeral system was flexible enough for vast imperial tax systems, yet visual enough for farmers.

Mayans and the Magic of Base-20

Halfway across the world, the Mayan civilization in Central America developed one of the most sophisticated ancient number systems.

It was vigesimal (base-20), using dots for 1s and bars for 5s.

They had a concept of zero—represented by a shell symbol—before most of the world.

Their calendar system, based on cycles and mathematics, predicted astronomical events with startling accuracy.

They didn’t need contact with India or Babylon. They built their system from scratch.

Modern Numbers and the Digital Turn

Today’s world runs on binary—just 0s and 1s. Computers don’t need 10 digits; two are enough.

The binary system, first theorized by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in the 1700s, was inspired by ancient Chinese I Ching (Book of Changes)—a text based on yin and yang.

Now, binary is the language of code, AI (artificial intelligence), and blockchain.

But it all began with fingers, rocks, and knots.

Numbers Are More Than Math

Each number system was shaped by what people needed and what they believed.

The Babylonians used base-60 because it’s divisible by 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6—useful for geometry.

The Mayans tracked time in cycles; hence, their numbers were circular.

The Indians saw philosophical depth in zero, while Europeans feared it as chaos.

Even today, the way we teach math, design software, or talk about inflation is shaped by these histories.

Conclusion: Recounting What Counts

The story of numbers is the story of civilization—of merchants, astronomers, priests, warriors, and schoolchildren. It’s a story of how we organize life, assign value, and make sense of the universe.

So, the next time you check your bank balance or solve a Sudoku puzzle, remember: you’re not just using numbers. You’re participating in a global, 40,000-year-old conversation about what matters and what doesn’t.

What we count tells us who we are.

Author’s Note

This blog was written to highlight how something as universal as numbers carries deeply human stories—of invention, resistance, trade, and even fear. If you’ve ever struggled with math, remember: you’re not alone. We all had to learn how to count—some of us with fingers, others with stars.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- The Story of Mathematics – A Brief History

- Smithsonian Magazine – Who Invented Zero?

- BBC – Numbers: The Universal Language

- https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Arabic_numerals

- https://news.ycombinator.com/item%3Fid%3D13131826

- https://hkage.org.hk/webbasedlearning/learningcourse/ext/3/v2/eng/numberTheory/chapter05_lesson10_01.php