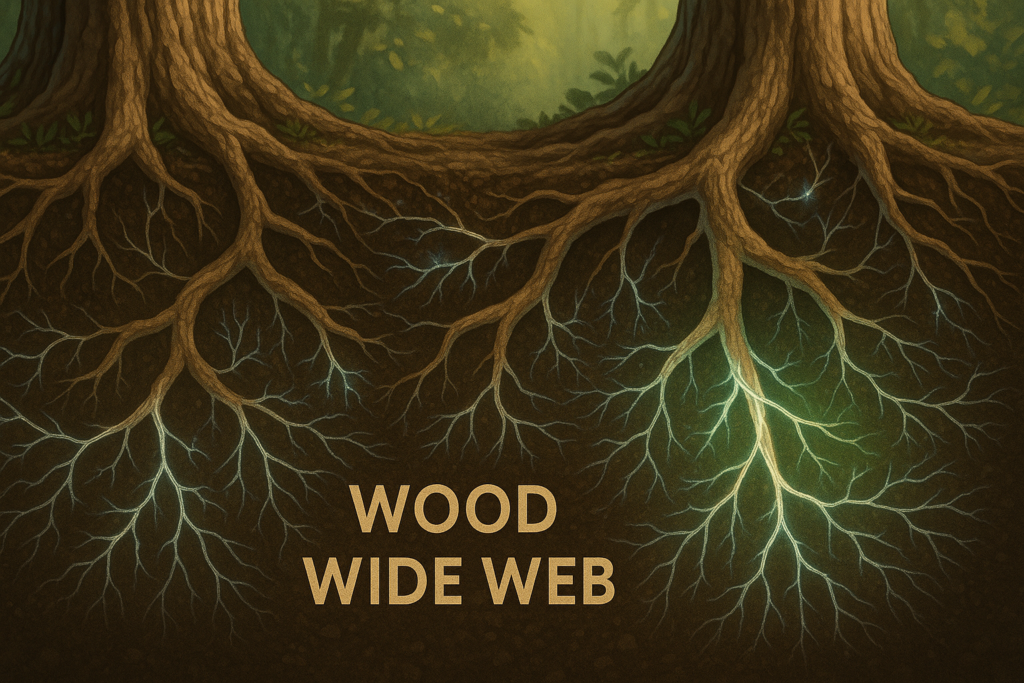

Fun fact: A forest can “talk”—trees share nutrients and send warnings through underground fungal networks.

If that sounds like a scene from Avatar, think again. It’s real. Scientists call it the “Wood Wide Web”, and it’s just one of many clues that suggest something extraordinary: nature may be far more intelligent than we’ve ever imagined.

The idea that “Nature has its own intelligence” challenges centuries of belief. We’ve long thought of intelligence as a uniquely human trait, or at best, something reserved for animals with brains. But what if intelligence isn’t just in the brain? What if it lives in roots, rivers, fungal threads, and coral reefs?

This blog invites you to entertain a radical but increasingly scientific idea—that nature might be not just alive, but aware.

Redefining Intelligence: Beyond IQ and Neurons

For generations, intelligence meant logic, language, or memory—skills measured by IQ (Intelligence Quotient) tests and attributed to humans and a few “smart” animals.

But scientists now argue that this definition is narrow, culturally biased, and biologically outdated. Intelligence, they say, isn’t just about test scores or brain size. It’s about adaptation, problem-solving, communication, and cooperation.

By that standard, ecosystems are brilliant.

The Mycorrhizal Internet: Trees That Talk

Let’s start with forests. Deep underground, tree roots are connected by networks of mycorrhizal fungi, which link entire ecosystems together. Through these networks:

- Older trees send nutrients to younger ones.

- Injured trees trigger alerts to their neighbours.

- Some species even recognise their own “kin” and support them more.

This is not random. It’s selective, purposeful, and reciprocal—hallmarks of intelligence.

Scientists like Dr. Suzanne Simard from the University of British Columbia have spent decades documenting how trees “decide” where to send resources, whom to help, and when to warn others.

So if a forest shares information, cares for its young, and adapts to threats—isn’t that a kind of wisdom?

Slime Mold Solves Mazes (Without a Brain)

You read that right. Slime Mold, a single-celled organism with no brain, is capable of solving mazes, finding the shortest paths between food sources, and even demonstrating a kind of memory based on past encounters.

In one experiment, Japanese scientists placed slime Mold in a petri dish with oat flakes arranged like train stations on a map of Tokyo. The Mold grew to connect the oats in a pattern eerily similar to the city’s rail system.

This isn’t luck. It’s logic—without neurons. It suggests that intelligence can emerge from organisation and interaction, not just brain cells.

Plants That “See,” “Hear,” and “Smell”

We often think of plants as passive. But science tells a different story.

- Mimosa pudica (the “touch-me-not”) remembers repeated stimuli and stops responding to harmless touches—demonstrating memory.

- Some flowers change their nectar sweetness when they “hear” bees buzzing nearby.

- Dodder vines can “smell” nearby plants and choose their host based on scent.

Plants use chemical signalling, light perception, and mechanical sensing to navigate their environments. That’s perception, memory, and choice—not just instinct.

Animal Architects and Cultural Transmission

From termite mounds to beaver dams, animals have long displayed creative intelligence. But what’s really surprising is cultural intelligence—the passing of knowledge across generations.

- Crows teach each other tool use.

- Whales have regional “songs” that evolve over time.

- Elephants hold funerals and remember routes even after decades.

These aren’t random behaviours. They’re inherited, shared, and learned—components of a collective intelligence.

Nature’s Problem-Solving Systems

Think about how a coral reef recovers after a bleaching event, or how a savanna rebalances after drought. These are complex systems with feedback loops, contingency planning, and resilience mechanisms.

Ecosystems respond, rebuild, and reorganise. They don’t just survive—they adapt. That’s intelligence.

In fact, many engineers now use biomimicry—design inspired by nature—to solve human problems. Algorithms mimic ant foraging. Aeroplanes mimic bird flight. Cities are now being planned using principles from termite ventilation.

Nature thinks. We copy.

Case Study: The Amazon Rainforest as a Self-Regulating System

The Amazon isn’t just a “lung” of the planet. It’s a self-regulating entity.

Trees there don’t just grow—they create their own weather. They release moisture that forms clouds, which rain back down to support the forest. This cycle isn’t controlled by any one organism, but by a collective intelligence that keeps the whole system in balance.

When parts of the forest are cut, the feedback breaks. Less rain falls, drought spreads, and fires increase. The system’s wisdom unravels.

A Different Kind of Consciousness?

So, is nature “conscious”? That depends on how you define it.

Philosophers and scientists are beginning to explore panpsychism—the idea that consciousness might be a fundamental feature of the universe, not limited to brains.

Others talk of distributed cognition, where intelligence arises from connections, not central control.

Even in technology, we’re seeing a shift. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is becoming less about human imitation and more about swarm behaviour, self-learning, and adaptation—traits nature has mastered for billions of years.

Perhaps what we call “nature” is not just a backdrop, but a mind in motion.

What This Means for Us

If nature is intelligent—truly intelligent—then our relationship with it has to change.

We’re not the “smartest” species managing a mindless world. We’re part of an ancient, sophisticated network of life that’s been solving problems long before we arrived.

This perspective demands humility—and responsibility. When we destroy forests, pollute rivers, or warm the atmosphere, we’re not just harming resources. We’re interrupting wisdom.

Nature isn’t just scenery. It’s a strategy.

Conclusion: Listening to the Living World

So what if nature does have its own intelligence?

It doesn’t mean we’ll be chatting with trees any time soon. But it does mean that every leaf, root, and ripple could be part of something thinking, learning, and evolving.

The next time you walk through a forest, swim in the sea, or plant a seed—remember, you’re not just interacting with a “thing.” You’re entering a conversation with a living, thinking system.

Are we ready to listen?

Author’s Note

The more we understand nature, the more it begins to resemble something we used to call “magic.” Perhaps the real magic is simply the intelligence we haven’t yet learned to recognise. Let’s be curious enough to ask—and humble enough to learn.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- Suzanne Simard’s TED Talk: How Trees Talk to Each Other

- The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben

- A Fungal Future. https://trintimes.ca/science/a-fungal-future/