Fun Fact: A single drop of glacier meltwater can take weeks—or even years—to reach your kitchen tap!

We turn on the tap and out comes water, clean and ready to drink. But have you ever wondered where it came from? Not just the city reservoir or the water tank, but really—where?

In this blog, we follow the incredible journey of a river, from its first breath as a drop of glacial melt high in the mountains, down through valleys, past cities, into treatment plants, and finally into our cups. “The Life of a River: Following Water From Glacier to Tap” is not just a scientific tour. It’s a story of life, loss, and everything in between.

Because when we truly understand where water comes from, we begin to realise something profound: every sip is a miracle—and a responsibility.

Birth: The Glacier’s Gift

The story begins thousands of meters above sea level, where ancient glaciers—massive, slow-moving rivers of ice—quietly sculpt the mountains. These frozen giants are nature’s water towers, storing centuries of snowfall and releasing it drop by drop as they melt.

For instance, the Gangotri Glacier feeds the Ganges River in the Himalayas, one of India’s most sacred and vital lifelines. Similar stories play out in the Andes, the Rockies, and the Alps.

As temperatures rise with the sun, glacier ice melts, forming trickles that gather strength into mountain streams. This isn’t just runoff. It’s the start of a journey through ecosystems, communities, and economies.

Youth: Tumbling Through Valleys

Once the water begins to flow, gravity becomes its closest companion. These youthful rivers are wild—crashing down steep slopes, carving through rocks, gathering sediment, and nourishing alpine vegetation.

In this stage, rivers are vibrant and untamed. They create habitats for trout, otters, and rare amphibians. But they also face early challenges. Deforestation, mining, and unchecked tourism in high-altitude zones have begun polluting what should be pristine headwaters.

A 2022 study by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) found alarming levels of microplastics and chemical contaminants even in glacier-fed streams once thought untouched.

What starts clean doesn’t stay clean for long.

Adolescence: Meeting People, Shaping Civilisations

As the river leaves the mountains and enters the plains, it begins to slow and broaden—both literally and metaphorically. This is where rivers become lifelines. They irrigate fields, power hydroelectric plants, and become transport corridors. They also begin encountering human waste, industrial effluents, and religious offerings.

Take the Yamuna River, which flows past Delhi. Born clear in the Himalayas, it becomes a sludge of sewage by the time it leaves the city.

And yet, despite our abuse, rivers remain generous. They keep flowing.

Adulthood: The River Becomes a System

By the time a river nears major cities, it’s no longer just a natural phenomenon—it’s a managed resource. Dams control its flow. Canals siphon its strength. Treatment plants try to fix what we’ve broken.

This is the invisible infrastructure beneath our modern lives:

– Water Treatment Plants (WTPs) remove pathogens and chemicals.

– Municipal Corporations manage distribution pipelines.

– Companies like VA Tech Wabag Ltd (an Indian multinational involved in water treatment) build systems to make river water safe for consumption.

But not every drop makes it. Some is lost to leaky pipes. Some to evaporation. Some never makes it past the dam gates, held hostage for hydropower or agriculture.

The river is now a resource. But at what cost?

Old Age: The Delta’s Last Breath

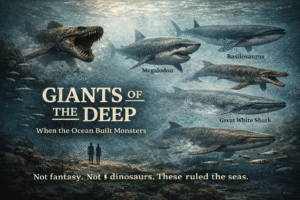

Eventually, the river reaches its delta—a slow, silty sprawl where it kisses the sea. But in recent decades, many rivers are dying before they get there.

The Colorado River in the United States (U.S.), for instance, no longer reaches the sea most years. The same fate looms for the Indus and the Krishna. So much is extracted upstream that the river dies of thirst before completing its journey.

This isn’t just poetic. It’s an ecological collapse.

Deltas are among the most productive ecosystems on Earth. They buffer against cyclones, provide fertile farmland, and support fisheries. When a river dies before the delta, everything that depends on it begins to wither.

Rebirth: Tap to Toilet to Treatment

You might think the story ends when the water reaches your tap. But in a circular economy, even used water has a second life.

After being used in homes, schools, and factories, wastewater is sent to Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs), where it can be partially or fully recycled. In forward-thinking cities like Chennai and Singapore, recycled water is used for industrial cooling and even made potable again.

But in many parts of India, untreated sewage is dumped right back into rivers—starting a toxic loop.

We treat rivers as one-way highways. But water, like life, is cyclical.

Case Study: The Mithi River, Mumbai

The Mithi River, running through Mumbai, is a perfect example of how urban neglect chokes a river’s life. Once a thriving estuarine stream connecting Powai Lake to Mahim Creek, it’s now infamous for flooding and pollution.

In 2005, Mithi’s choked flow contributed to catastrophic flooding that paralysed Mumbai. Since then, efforts have been made to desilt and clean the river, but industrial waste and encroachment continue.

It’s a cautionary tale—and a call to act.

What Rivers Teach Us (If We Listen)

Every stage of a river’s life is a lesson:

- From the glacier: Patience and quiet strength.

- From the valley: Power and purpose.

- From the plains: Generosity and resilience.

- From the tap: Trust and dependence.

- From the delta: Fragility and finality.

A river lives many lives before it reaches you. Shouldn’t we honour that?

Conclusion: We Don’t Own Water. We Borrow It.

Water doesn’t begin with us, and it shouldn’t end with us either.

When you next turn on the tap, take a moment to think about its journey—from glacial melt, through forests, farms, factories, cities, and filters. That drop has seen more than most of us ever will. And it’s still not done.

If we want rivers to keep flowing, we have to change how we treat them—not as commodities, but as companions.

Because the life of a river is also the story of ours.

Author’s Note

This blog was inspired by a trek near the source of the Bhagirathi River, where I first saw a glacier crack and melt into a trickle. That trickle might’ve become someone’s morning chai. That realisation has stayed with me—and now, I hope, it stays with you.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- ICIMOD – The Health of the Himalayan Rivers

- UN Water – The Role of Deltas in Sustainable Development