Fun fact: one ton of burnt paddy straw releases the same amount of CO₂-equivalent as driving around the M25 motorway in the UK for a week.

Now imagine that same straw instead becoming fuel. In “Green Hydrogen from Straw: When Crop Waste Becomes Fuel”, the bold new memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the Punjab Energy Development Agency (PEDA) and the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) turns this idea into action—using agricultural residue to produce green hydrogen. It’s a potential game-changer for how we manage farm waste, fight air pollution, and fuel the future.

Why straw? A problem turned opportunity

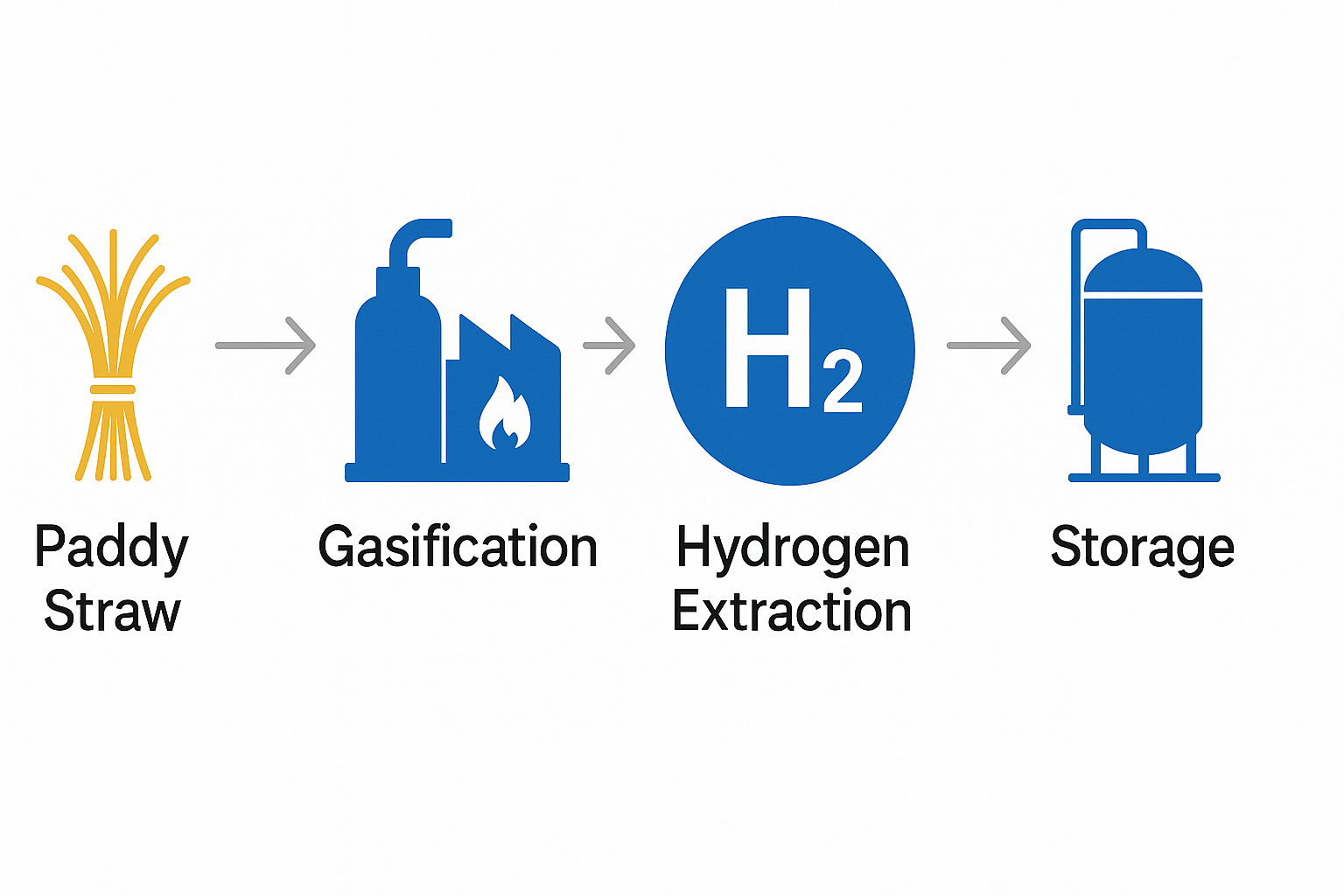

Each harvest season, millions of tonnes of paddy straw sit in the field or get burned in states like Punjab, releasing haze, particulate matter and greenhouse gases. The MoU between PEDA and IISc tackles this head-on by turning paddy straw into green hydrogen—the kind of fuel that emits only water when used. The pilot will demonstrate how waste becomes resource, stubble burning becomes obsolete, and farmers become partners in the green economy.

By using straw instead of fossil feedstock, this project addresses at least three crises simultaneously: crop-residue disposal, air quality degradation and the need for low-carbon energy. In effect: waste enters one end, clean fuel emerges the other.

How the pact works: case study in action

Under the agreement, PEDA will collaborate with IISc’s Interdisciplinary Centre for Energy Research (ICER) to set up a pilot facility that produces green hydrogen from biomass—mainly paddy straw. The idea: establish a demonstration unit to check technical and commercial viability. The MoU is strategic: not just a lab exercise but something that could scale and replicate across India.

This kind of innovation slices through silos: agriculture meets energy, rural livelihoods meet industrial feedstock, waste meets resource. For farmers, it offers an extra income stream instead of open-field combustion; for the energy sector, it offers renewable hydrogen without depending solely on solar or wind; for communities, it promises cleaner air and fewer toxic haze days.

Anecdote: The farmer who burns less and earns more

Picture this: Late-October, harvest season. A farmer finishes threshing, his field full of left-over straw. Normally he would set it alight, tighten his scarf around his face against the fumes, and wait for authorities to ‘make him stop.’ Under the new model, that same straw gets collected, weighed, and sold to the pilot hydrogen plant. He tells me: “If they pay me 2 rupees per kilo for straw, I’ll skip the fire.” He hasn’t signed any deal yet, but the promise of income and cleaner air changes the mood.

Why it’s provocative

Because it challenges assumptions. We think of hydrogen as high-tech, imported, expensive. Here, hydrogen is home-grown, from fields. We think of crop residue as a burden, a problem. Here, it becomes feedstock, value. We think of farmers as victims of pollution. Here, they become part of the solution. The project asks: why burn when you could earn? Why pollute when you could power?

And importantly: why wait for an industrial-scale mega-project when you can pilot at farm-scale and iterate? It’s bold—and it forces us to ask: are traditional energy players ready to integrate agriculture and waste?

The hurdles and what to watch

Of course, conversion of straw to hydrogen is not without challenges:

Feedstock logistics: Collecting, transporting and storing paddy straw is labour-intensive and seasonal. The pilot must design efficient supply chains to make it viable.

Technology & cost: Green hydrogen from straw still faces hurdles in conversion efficiency, purity, cost of electrodes or catalysts, and integrating with existing systems.

Commercial viability: Even if the technology works, can the hydrogen compete with conventional fuels or hydrogen produced via electrolysis powered by renewables?

Regulatory & policy frameworks: The project touches agriculture, energy, environmental norms. Coordination across ministries and state policies will matter.

Scaling up: A pilot is one thing; replicating across states, crops, seasons is another. Yield, variation in crop residue, crop-types, burden of logistics differ by region.

If the pilot gets these right, however, it could become a template for other states and regions. That’s the value of the MoU: it says “let’s test, learn, scale.”

What this means for India’s energy and agriculture future

India’s push for a hydrogen economy is real. The National Green Hydrogen Mission aims to build capacity, cut fossil dependence and lead in clean fuels. Add to that the vast amount of agricultural residue annually: the two marry nicely. If the PEDA-IISc project succeeds, we could see a model where farmers supply hydrogen feedstock, rural economies grow, crop burning declines and energy systems diversify.

This could also shift the narrative around agriculture: where farmers are not just feeding the nation with food, but also energising the nation with fuel. The pilot could trigger investment, skill-development in rural areas, new jobs in hydrogen tech, and a new value chain for straw.

Conclusion

In Green Hydrogen from Straw: When Crop Waste Becomes Fuel, the PEDA-IISc partnership isn’t just another MoU—it’s a statement of intent. It says: agricultural residue doesn’t have to be a problem. It can be a solution. It says: energy and farming can converge, not clash. It says: rural incomes, pollution control and clean fuel can rise together.

If this pilot delivers, then those smoky field evenings and emergency stubble-burning bans may become relics of the past. Farmers may see straw trucks instead of fire trucks. Hydrogen plants may see bale-feedstock instead of fossil feedstock. And the air we breathe may become a little cleaner.

But it won’t happen by chance. It needs support—from policy, from investment, from farmers, from engineers, from civic awareness. So here’s the ask: keep an eye on this project, ask your local farm-centre or energy office how they will replicate it. Because when crop waste becomes fuel, our energy future becomes more than sunshine and wind—it becomes circular, rural-friendly and resilient.

Author’s Note

I spent a season watching stubble burn across fields and counting the haze that followed. The idea that the same straw could one day power buses or factories seemed far-fetched. Now it doesn’t. This project is a little daring, a little messy, and exactly the kind of change we need. I hope we listen.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.