Fun Fact: Starbucks didn’t just sell coffee—it once marketed itself as a “third place” between home and work, where people could simply be.

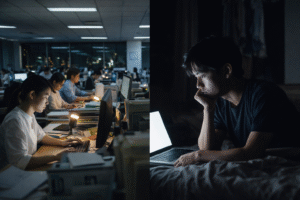

Home is where the heart is. Work is where the paycheck comes from. But where do we go just to be?

Welcome to the idea of the “third place.” First introduced by sociologist Ray Oldenburg in the 1980s, this concept refers to informal public gathering spaces that are neither home (the “first place”) nor work (the “second place”). Think of cafes, libraries, parks, barber shops, co-working lounges, community gardens, and even gaming arcades. The rise of the third place is more than a nostalgic yearning for chai at the corner tea stall. It’s a vital shift in how we think about community, connection, and our collective mental health.

In an age of remote work, digital overload, and social disconnection, third places are becoming not just relevant but essential. So why have we neglected them for so long—and what will it take to bring them back?

What Exactly Is a Third Place?

A third place is an informal public space where people come together voluntarily for conversation, relaxation, entertainment, or simply to exist in the presence of others. They’re low-stakes, inclusive, and open-ended. Unlike work, there’s no pressure to perform. Unlike at home, there’s no obligation to host.

In Indian cities, third places used to be everywhere: local chaiwalas, roadside libraries, old cinema halls, gully cricket grounds, and temple courtyards buzzing with intergenerational gossip. But as cities gentrify and public land shrinks, these spaces are being replaced by malls, gated communities, and members-only clubs.

Today’s urban environments are optimised for productivity, not presence. Yet presence—just showing up and being seen—is what makes us human.

The Decline of Third Places in Modern India

Urbanisation has come at a cost. As more people migrate to cities, public space has become increasingly privatised. Malls masquerade as public gathering spots but are curated for consumers, not citizens. Cafés have Wi-Fi, but it is not always welcome. Meanwhile, the local park is either underfunded, overpoliced, or simply bulldozed.

This erosion is especially stark in India’s metros. Bengaluru’s lakeside benches are slowly being replaced by tech campuses. Delhi’s historic nukkads (street corners) are disappearing under flyovers. In Mumbai, where every square foot is premium real estate, there’s little room for loitering unless you’re paying for the privilege.

Add to that the cultural stigma around “doing nothing,” especially among the younger generation constantly nudged to hustle—and the idea of leisurely hanging out in a neutral space begins to feel rebellious.

Why Third Places Matter More Than Ever

Social Glue in a Fragmented World

As loneliness becomes a public health crisis, third places offer natural settings for organic interaction. You don’t need an invitation or a reason. You just show up. In doing so, you build relationships across age, class, caste, and culture.

Mental Health Buffers

Being in public spaces, especially ones that don’t require performance or consumption, has proven psychological benefits. They reduce anxiety, offer a sense of routine, and help fight the alienation of digital life.

Community Resilience

During crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, cities with stronger networks of community centres, temples, mosques, gurdwaras, and local halls responded more quickly and humanely. These third places became food distribution hubs, vaccination sites, and emotional anchors.

Incubators for Ideas and Democracy

Some of the world’s most radical ideas have taken root in cafés and clubs. From India’s independence movement brewing in Kolkata’s Coffee House to student-led debates in JNU’s (Jawaharlal Nehru University) canteen, third places foster freedom of thought and exchange.

The New-Age Third Places: Reinvention or Imitation?

In today’s hyper-commercial world, some brands have tried to replicate third places—for better or worse.

WeWork India (a branch of the global co-working brand WeWork, which provides flexible office spaces) has designed “community lounges” that blend the social aspects of a café with the utility of an office. But with high membership fees, the accessibility is limited.

The Social (a café-bar-coworking hybrid run by Impresario Handmade Restaurants) markets itself as a hangout zone for millennials. It offers plug points, board games, quirky décor, and event nights. But again, it caters to a very specific demographic.

Ranga Shankara in Bengaluru and Prithvi Theatre in Mumbai are rare gems—third places built around the arts where tickets are affordable, food is subsidized, and strangers often become friends. They show that cultural engagement can be inclusive and democratic.

The risk, of course, is that once third places become curated experiences tied to branding strategies, they stop being truly free. The magic of the third place is in its messiness, its accessibility, and its lack of agenda.

India’s Local Third Place Champions

Let’s not ignore the homegrown heroes:

Khoj International Artists’ Association in Delhi supports emerging artists with open studios, exhibitions, and informal meet-ups.

Spaces like Harkat Studios in Mumbai host everything from poetry nights to potlucks—no membership required.

Library Movement in Kerala, which includes more than 8,000 local libraries, functions as a democratic third place and a knowledge sanctuary.

We need more such initiatives—and more funding, policy, and cultural support to protect and proliferate them.

Making Room for the Third Place

So, how do we reclaim third places in our cities and towns?

Policy-Level Interventions:

Urban development must include social infrastructure, not just roads and metros. Municipal corporations should zone areas for free public use and provide maintenance budgets.

Designing for Pause, Not Just Passage:

Streets shouldn’t just connect homes to workplaces. They should have benches, trees, tea stalls, and shade.

Encouraging Local Stewardship:

Resident welfare associations (RWAs), NGOs, and schools can be given incentives to turn underused community spaces into third places—gardens, libraries, or activity centres.

Cultural Reframing:

Loitering isn’t laziness. Hanging out isn’t a crime. We need to reclaim the dignity of unstructured time and neutral space, especially for youth, women, and the elderly.

Conclusion: Why We Need More ‘In Between’ Spaces

The rise of the third place is not just about nostalgia. It’s about need.

In an era when home is shrinking (think studio apartments), work is exhausting (or remote), and loneliness is epidemic, we need more in-between spaces. Not just physical ones, but emotional sanctuaries—places that invite us in without asking us to buy something, achieve something, or explain ourselves.

Because sometimes, being seen by strangers over a cup of chai is more healing than any Zoom call.

Let’s make space—for the third place.

Author’s Note:

I wrote this piece while sipping overpriced filter coffee in a crowded café with nowhere else to go. This blog is a gentle nudge to reimagine how we live together—and how we might reclaim some joy in just being.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading:

- Oldenburg, R. (1999). The Great Good Place. Marlowe & Company.

- “Why Third Places Are Important.” Project for Public Spaces. https://www.pps.org/article/what-is-a-third-place

- “India’s Vanishing Third Places.” Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/849199/indias-vanishing-third-places