Fun fact: Ancient Babylonians predicted lunar eclipses with precision—more than 2,500 years before the invention of the telescope.

Imagine trying to map the heavens with nothing but your eyes, a few sticks, and unwavering patience. No telescope. No clock. No calculator. Just intuition, observation, and a deep, almost spiritual, relationship with the sky.

Yet, somehow, ancient astronomers managed to track the movements of the planets, predict eclipses, calculate solstices, and even estimate the Earth’s circumference—all without high-tech tools. In this blog, we’re diving into what ancient astronomers got right without telescopes and how their insights continue to awe scientists today.

Stargazing Wasn’t Just a Hobby—It Was Survival

In ancient times, astronomy wasn’t a field of science. It was a matter of survival and power.

Agricultural cycles depended on the stars. Navigation across deserts and seas relied on the night sky. Kings and priests used celestial patterns to justify wars, festivals, and political decisions. The heavens were calendars, compasses, and cosmic instruction manuals all rolled into one.

And because the stakes were high, people paid attention—obsessively.

The Babylonians: Masters of Celestial Cycles

Let’s start in ancient Mesopotamia.

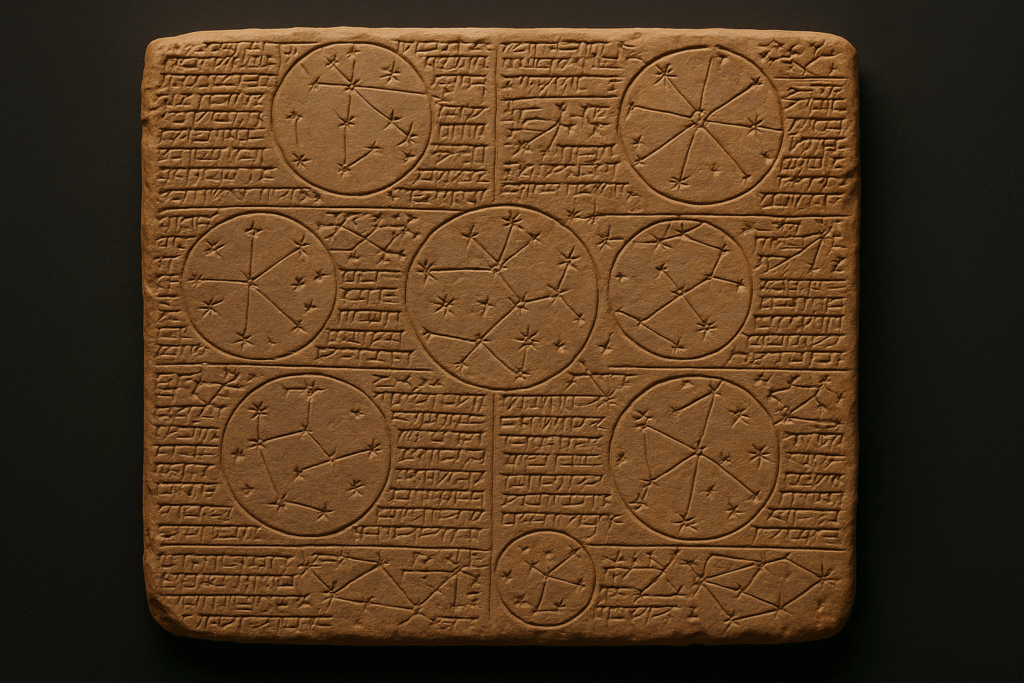

By 500 BCE (Before Common Era), Babylonian astronomers had already created accurate mathematical models for predicting lunar eclipses using a cycle known as the Saros (approximately 18 years). Without any optical aid, they knew that after a specific number of days, the moon would darken again.

How? They kept meticulous records. For generations, Babylonian scribes tracked planetary motions, compiled data on eclipses, and recognized patterns in the chaos.

They even had a concept of the zodiac—dividing the sky into 12 segments corresponding to constellations. Sound familiar?

India: Astronomy Woven into Spiritual Thought

In ancient India, astronomy (known as Jyotisha) was both science and scripture.

Texts like the Surya Siddhanta, composed around 400 CE (Common Era), provided incredibly precise astronomical calculations. Indian astronomers like Aryabhata (5th century CE) calculated the length of the solar year to be 365.358 days—remarkably close to the modern value of 365.2422 days.

Aryabhata also proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis, a revolutionary idea centuries before it gained traction in Europe. He even offered a near-accurate explanation for solar and lunar eclipses, describing them in terms of shadows rather than divine punishment.

Without telescopes, Indian astronomers relied on geometry, trigonometry, and systematic observation—tools powerful enough to pierce the cosmos.

The Greeks: Math as a Telescope

The ancient Greeks didn’t just observe—they calculated. They built models.

Take Eratosthenes (3rd century BCE), who estimated the Earth’s circumference using nothing but sticks, shadows, and brainpower. By comparing the angle of the sun’s rays in two different cities (Alexandria and Syene), he concluded that the Earth was spherical and surprisingly accurate in its size estimation.

Then there’s Hipparchus (2nd century BCE), who invented trigonometry, created the first star catalogue, and even measured the precession of the equinoxes—detecting that the Earth’s orientation shifts over time.

Oh, and he did all this more than 1800 years before the telescope was invented.

China: Celestial Bureaucracy

In ancient China, astronomy was a state business. The emperor’s right to rule (the “Mandate of Heaven”) was tied to celestial harmony, so astronomical records were as vital as tax receipts.

Chinese astronomers documented supernovae (like the one in 1054 CE that created the Crab Nebula), recorded sunspots, and tracked the positions of planets with high precision. They divided the sky into 28 “lunar mansions,” a system similar to the zodiac but rooted in distinctly Chinese cosmology.

They even built large-scale instruments like the armillary sphere—an early model of the universe, complete with rotating rings to represent the celestial sphere.

The Maya: Astronomers of Time

Across the world, the Maya civilization in Central America built a calendar so accurate that it rivals the Gregorian calendar we use today.

The Dresden Codex, one of the oldest surviving American books, contains tables that accurately predict solar eclipses, Venus cycles, and equinoxes. The Maya knew that Venus had a cycle of about 584 days—and used it to time wars and rituals.

Their observatories, like El Caracol in Chichen Itza, were aligned with celestial events, showing a sophisticated understanding of planetary motion and seasonal changes—all without glass lenses.

The Tools of the Trade: No Telescopes, Just Ingenuity

Ancient astronomers used clever tools like:

Gnomons: Vertical sticks used to measure shadow lengths and track the sun’s movement.

Sundials: Timekeeping using sunlight angles.

Astrolabes: Used by Islamic astronomers to measure the altitude of stars and planets.

Star charts: Hand-drawn maps tracking celestial bodies, sometimes passed down for generations.

Sightlines in architecture: Temples and pyramids aligned with solstices or star risings.

These tools may seem primitive, but they were powered by one priceless thing: patience. Ancient astronomers watched the sky over decades—sometimes over generations—handing down observations like sacred texts.

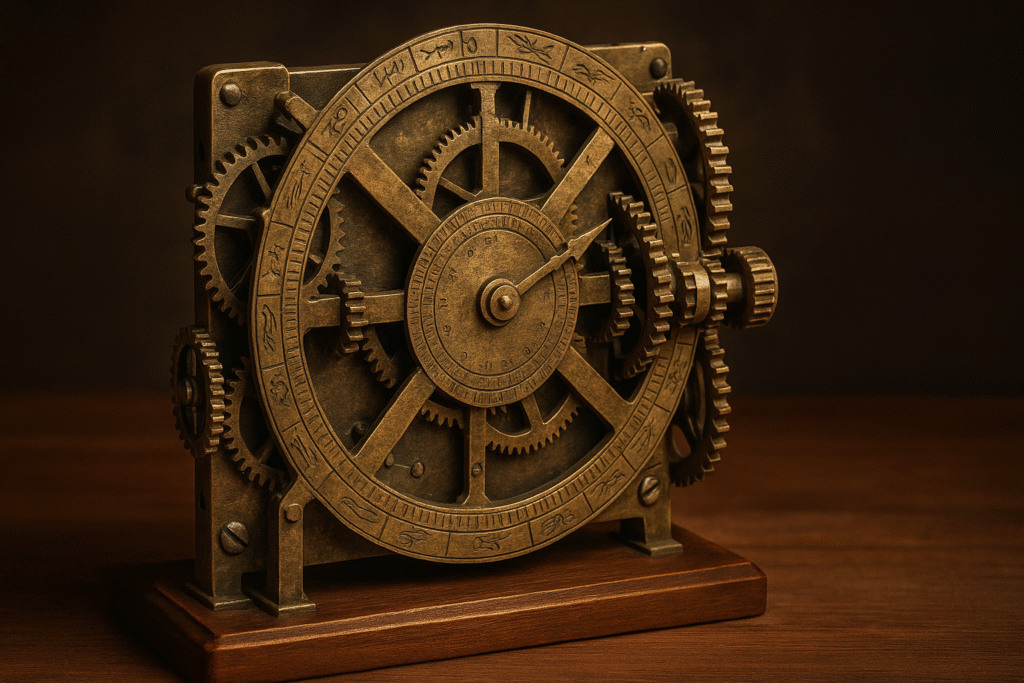

Case Study: The Antikythera Mechanism

Discovered in a shipwreck off the coast of Greece in 1901, the Antikythera Mechanism is an ancient analogue computer, built around 100 BCE. It could predict solar eclipses, track lunar phases, and even model the irregular orbit of the moon.

It contained over 30 bronze gears, all hand-cranked. Modern researchers still marvel at its complexity.

This wasn’t just ancient astronomy—it was ancient engineering, centuries ahead of its time.

What They Got Right—and Why It Matters

So, what exactly did ancient astronomers figure out without telescopes?

- The Earth is spherical.

- The solar year is roughly 365 days.

- Planets move in complex patterns (retrograde motion).

- Eclipses are predictable.

- The moon affects tides.

- The stars shift over long timescales (precession).

- The calendar can be used to guide agriculture and ritual.

These aren’t trivial facts. They’re the foundation of science, calendars, agriculture, and even global navigation.

They remind us that intelligence doesn’t require modernity. That genius can shine through even when all you have is the night sky.

Conclusion: Eyes to the Sky, Feet in the Dust

In a world obsessed with high-tech tools, it’s humbling to remember that some of our greatest insights came not from machines, but from minds.

Ancient astronomers, without telescopes, cracked cosmic codes using nothing but math, observation, and faith in patterns. They made the sky their classroom and the stars their syllabus.

So maybe tonight, take a moment. Look up. You’re staring at the same canvas they once studied—and the same mysteries they tried to solve.

And they did it without a telescope.

Author’s Note

Researching this reminded me that progress isn’t always about invention—it’s often about attention. The ancient world watched closely. And because of that, they saw far.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- NASA – Ancient Observatories

- Scientific American – Ancient Astronomy’s Achievements

- . https://www.deepermind.com/T2/Astronomy1.html