Fun Fact: The idea of “protected areas” in India owes much to forest policies made during the British colonial era—long before modern ideas of community rights entered the picture.

In the contested terrain of environmental protection, the headline “When Forests Become No-Go Zones (for Locals): The Politics of Conservation” calls out a stubborn contradiction. On one hand, governments and conservation bodies talk of saving habitats, wildlife and ecosystem services. On the other, they often enact rules that exclude, displace or marginalise the very people who have lived in and with those forests for generations. The question is: when preservation becomes exclusion, whose forest is it really?

Conservation as Exclusion: The Framing

Conservation has often been framed as a battle between humans and “wild nature”, where the safest strategy is to fence off forests, evict people, and bar local practices like grazing, shifting cultivation, minor forest produce collection. Researchers term this “regime of exclusion”. In India alone, one analysis found that between 1999–2020, around 13,445 families were displaced from 26 protected areas.

This is not just removing people from land—it removes rights, agency, livelihoods, and recognition.

Case Study: The Cost to Local Communities

Let’s zoom into examples. When the Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA) was enacted to recognise the rights of forest-dwelling communities and Indigenous Peoples, the hope was for inclusion. Yet many conservation schemes continue to treat forest people as intruders. A study of two Indian protected areas showed that displaced communities suffered impoverishment, loss of livelihood and social disintegration.

For example, a resident once said: “They told us the forest is for the tigers now. We were just living there.” The message: the forest might be “protected”, but the people weren’t.

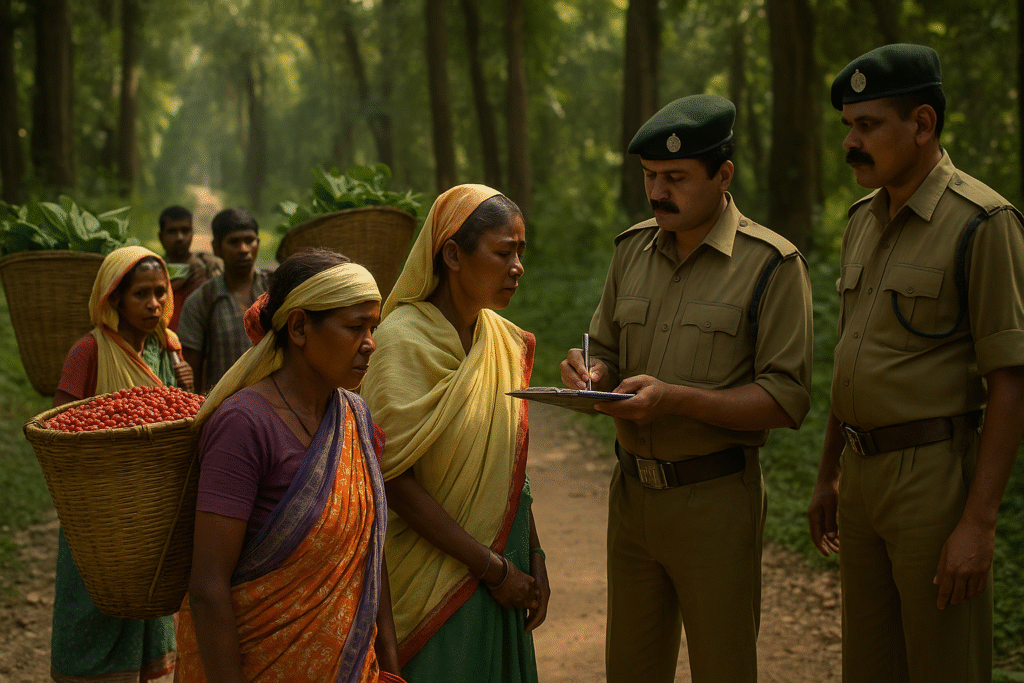

Marginalisation in Practice: Exclusion Beyond Eviction

Displacement is only the tip of the iceberg. Many communities face restrictions on their customary practices—collecting non-timber forest produce, grazing livestock, or even entering certain forest zones. In Himachal-Uttarakhand, the Van Gujjar pastoral nomads have been repeatedly issued vacate notices, their traditional migratory rights contested in courts.

When you’re barred from your home, your livelihood, and your landscape, the forest becomes not sanctuary—but a barrier.

Geographies of Power: Who Makes the Rules?

A key tension lies in power and decision-making. Forest departments, conservation NGOs, global funding agencies often frame policies; local voices rarely lead. One report argues that exclusionary conservation “costs less” than inclusion—because inclusion would require power-sharing, compensation, and rights-recognition.

As long as the narrative remains “people vs nature”, the pendulum will continue to swing toward control, borders and banishment—rather than stewardship, dialogue and justice.

The Ecology Doesn’t Always Win, Either

You might think exclusionary conservation must produce wildlife victory. But not always. By alienating local communities, you lose stewards of the land. Local knowledge about fire regimes, species behaviours, seasonal cycles vanishes. The result can be worse environmental outcomes. Many argue that community-based conservation, where locals are partners not prisoners, yields better results.

So this isn’t just about fairness—it’s about effectiveness.

A Few Anecdotes: Lives in the Margins

- In central India, a tribal village near a tiger reserve still carries the stigma of “illegal” even though their families lived there for decades.

- In Assam and Meghalaya borderlands, locals say they now need permission to collect honey or bamboo, something their grandfathers did freely.

- Many women forest gatherers say they are now watched, fined, or barred from traditional routes—while tourists roam free in the same forests.

These voices matter because they can’t be captured in the statistics alone.

Conclusion: Conservation Must Be More Than Barriers

When forests become “no-go zones” for locals, conservation loses its moral and practical edge. The title – When Forests Become No-Go Zones (for Locals): The Politics of Conservation – isn’t a dramatic exaggeration. It’s a reality for many.

Here’s what needs to happen:

- A shift from exclusion to co-management: recognising local rights, voices and governance.

- Transparency and accountability: identify when “protected” means locked out—not helped.

- Justice for the marginalised: compensation, livelihood options, rights recognition must be core, not after-thoughts.

- Ecological purpose should include human purpose: healthy forests are entwined with healthy communities.

As readers, we should ask: when we admire a green forest photo on social media—who lives beneath that canopy? Are they part of the story, or excluded from it? Because until conservation opens its doors instead of closing them, the promise of forests remains half-fulfilled.

Author’s Note

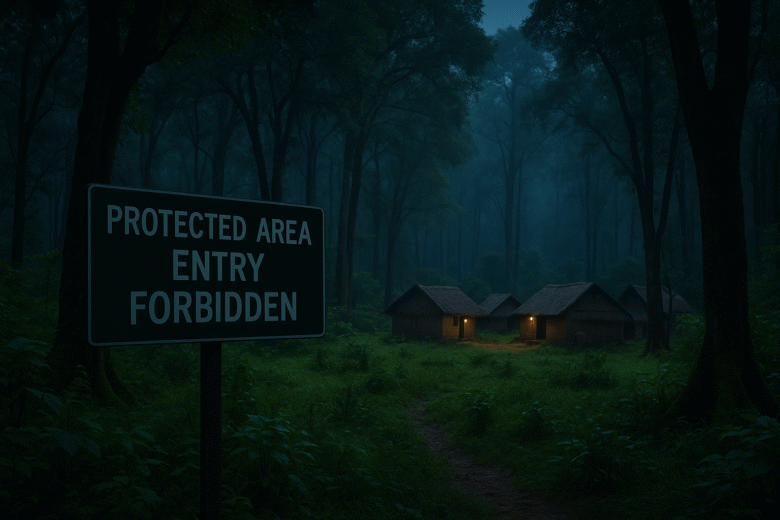

I walked—once, quietly—along a village path through a reserve forest, past signage that read “Entry Prohibited”. The irony struck: the community hadn’t been allowed access for years, yet the “forest protection” signage remained. Writing this piece mattered because I believe forests must protect people too—not just trees. Writing isn’t simply transmission of facts—it’s invitation to see, question and act.

G.C., Ecosociosphere contributor.

References and Further Reading

- Indian conservation ‘puts communities in peril’

- Protect & conserve model displaced 13,450 families from 26 protected areas in two decades

- Displacement and relocation from protected areas

- Conservation regimes of exclusion: NGOs and the role of exclusion in India’s conservation model

- Including local community in protecting forests costs less than excluding them: Report

- India’s shift to inclusive conservation of forests